Roger Eliot Fry (1866-1934)

On this page

This online exhibition will give a biographical sketch of the artist and critic Roger Fry, through his letters and other archives. Particular emphasis will be given to his family, friendships and training, all of which greatly influenced his work.

The exhibition is roughly chronological, meaning that the headings are somewhat imprecise and there may be slight overlap between sections.

Childhood

Roger Eliot Fry was born on 16 December 1866, to Sir Edward Fry (1827–1918) and his wife Mariabella (1833–1930). The second son of confectioner Joseph Fry (1795–1879), Edward was a successful judge and zoologist.

Francis Spalding, author of Roger Fry: Art and Life, characterises Roger Fry’s upbringing as being in a family which placed considerable value on work, austerity and faith. His family is notable among Quakers, as George Fox’s journals records that Roger Fry’s ancestor Zephaniah Fry (1658-1728) was arrested in 1683 for his involvement in a meeting of the Society of Friends.

Roger Fry’s earliest memories were of his first home, 6, The Grove, Highgate. In 1872, the family moved next door, to number 5, where the children could benefit from a larger garden. In 1875, they had their first visit to Failand House, a ‘summer home’ Roger’s parents had bought near Bristol.

Roger Fry went to Summerhill House, St George’s School, Ascot, at the age of 11, having been homeschooled until that point. Then, in 1881, he went to Clifton College, Bristol, where he became friends with John Ellis McTaggart.

His father encouraged him towards science. His mother enjoyed watercolours but what artistic influence he received as a child was generally from his wider family and his teachers. He and his siblings had annual visits to the Royal Academy and Charles Tomlinson, a family friend, took him to the National Gallery. His aunt Bessie’s husband was the Gothic Revival architect Alfred Waterhouse, who may have introduced him to some of the artistic and architectural tastes of the day.

![First page of an untitled memoir of skating with Sir Edward Fry at Kenwood Park in 1874. [REF/1/170] First page of an untitled memoir of skating with Sir Edward Fry at Kenwood Park in 1874. [REF/1/170]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_1_1539x1920.jpg)

![First page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168] First page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_2_1462x1920.jpg)

![Second page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168] Second page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_3_1455x1920.jpg)

![Third page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168] Third page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_4_1477x1920.jpg)

![Fourth page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168] Fourth page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_5_1463x1920.jpg)

![Fifth page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168] Fifth page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_6_1483x1920.jpg)

![Fifth page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168] Fifth page of an untitled memoir of childhood at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/168]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_7_1470x1920.jpg)

![First page of an untitled memoir of the garden at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/169] First page of an untitled memoir of the garden at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/169]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_8_1483x1920.jpg)

![Second page of an untitled memoir of the garden at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/169] Second page of an untitled memoir of the garden at 6 The Grove, Highgate. [REF/1/169]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_9_1481x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 24 May 1885, describing a visit to the Waterhouses. [REF/3/57] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 24 May 1885, describing a visit to the Waterhouses. [REF/3/57]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_10.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 24 May 1885, describing a visit to the Waterhouses. [REF/3/57] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 24 May 1885, describing a visit to the Waterhouses. [REF/3/57]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_11.jpg)

King's

In December 1884, Fry spent a few days in Cambridge, sitting his scholarship examinations. On 22 December, he wrote home, telling his mother he had won a Natural Science scholarship. Little must he have known the cultural differences he would face and how they would influence his intellectual development and career.

Fry matriculated in 1885 and moved into lodgings on Trumpington St with McTaggart, who joined Trinity College. This worried Fry’s mother, who was concerned that McTaggart’s influence would test Fry’s faith.

Fry quickly formed a new friendship, with C.R. Ashbee. Ashbee and Fry were very different but it is clear that the former influenced the latter. They shared an interest in Gothic architecture and would visit buildings like Wells Cathedral together, often sketching. Both read Ruskin, although Fry would later become more critical of his writings. Ashbee introduced Fry to Edward Carpenter and they visited his home, Millthorpe, together. Carpenter was outspoken about socialism, homosexuality and comradeship. As Fry’s letter to his mother (below) shows, he was pleasantly surprised by Carpenter, who he had expected to be a ‘somewhat rampant and sensational Bohemian’. Fry also attended a lecture by G.B. Shaw. It may be Ashbee’s influence which led to Fry’s election to the Cambridge Fine Arts Society on 3 February 1886.

In 1887, Fry became friends with Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Nathaniel Wedd. Dickinson proposed that Fry be elected a member of a secret society called the Apostles.

Ashbee was older than Fry and when the elder left Cambridge, Fry’s friendship with Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson became stronger. Dickinson was interested in political philosophy, not art, but Fry was used to philosophical conversations with McTaggart and all three were members of the secret society, the Apostles (for an exhibition on the Apostles, see the link at the bottom of this page). Fry and Dickinson had a close friendship which lasted many years, but for Dickinson there was an attraction towards Fry which was not fully reciprocated.

In 1888, Fry designed the cover for the ‘Cambridge Fortnightly’.

Fry was able to take a more scholarly interest in art after J.H. Middleton was appointed Slade Professor at Cambridge. Although he was studying Natural Sciences, Fry learned about Italian art from him and from visits to the Fitzwilliam Museum. When Fry gained a First, Middleton recommended that he stay in College and apply for a Fellowship, while also studying drawing. Fry wrote two fellowship dissertations but neither was successful. Although Fry was more keen to be an artist than a critic, Fry’s 1891 fellowship dissertation 'Some problems of phenomenology and its application to Greek art: a dissertation' hints at a meticulous theoretical approach to analysing art.

![Telegram from Roger Fry to his mother, 22 December 1884, concerning his scholarship. [REF/3/57/19] Telegram from Roger Fry to his mother, 22 December 1884, concerning his scholarship. [REF/3/57/19]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_12_2952x1920.jpg)

![Roger Fry’s entry in King’s College’s Senior Tutor’s book. [KCAC/4/1/1, p.30] Roger Fry’s entry in King’s College’s Senior Tutor’s book. [KCAC/4/1/1, p.30]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_13.jpg)

![McTaggart, John Ellis. [KCAS/39/4/1, Apostles Photobook, p. 66, no. 212] McTaggart, John Ellis. [KCAS/39/4/1, Apostles Photobook, p. 66, no. 212]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_14_1583x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 18 October 1885, concerning McTaggart and his own faith. [REF/3/57/21] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 18 October 1885, concerning McTaggart and his own faith. [REF/3/57/21]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_15.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 18 October 1885, concerning McTaggart and his own faith. [REF/3/57/21] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 18 October 1885, concerning McTaggart and his own faith. [REF/3/57/21]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_16.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 22 April 1888, expressing religious doubts. [REF/3/57/25] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 22 April 1888, expressing religious doubts. [REF/3/57/25]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_17.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 22 April 1888, expressing religious doubts. [REF/3/57/25] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 22 April 1888, expressing religious doubts. [REF/3/57/25]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_18.jpg)

![Ashbee’s journal entry on visiting Peterborough Cathedral with Fry, 15 June 1886. [CRA/1/2, 198] Ashbee’s journal entry on visiting Peterborough Cathedral with Fry, 15 June 1886. [CRA/1/2, 198]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_19_1503x1920.jpg)

![Ashbee’s journal entry, 26 June 1886. [CRA/1/2, 206 recto] Ashbee’s journal entry, 26 June 1886. [CRA/1/2, 206 recto]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_20.jpg)

![Ashbee’s journal entry, 26 June 1886. [CRA/1/2, 206 verso] Ashbee’s journal entry, 26 June 1886. [CRA/1/2, 206 verso]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_21.jpg)

![Part of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 25 July 1886, concerning Carpenter. [REF/3/57/23, iv 51 verso] Part of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 25 July 1886, concerning Carpenter. [REF/3/57/23, iv 51 verso]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_22.jpg)

![Part of a letter from Roger Fry to Ashbee, 22 October 1887, concerning socialism. [CRA/1/3, 152] Part of a letter from Roger Fry to Ashbee, 22 October 1887, concerning socialism. [CRA/1/3, 152]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_23.jpg)

![Dickinson, Goldsworthy Lowes. [KCAS/39/4/1, Apostles Photobook, p.65] Dickinson, Goldsworthy Lowes. [KCAS/39/4/1, Apostles Photobook, p.65]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_24.jpg)

![‘The Cambridge Fortnightly' no.3 vol.1, 1888, cover by Roger Fry. [REF/4/4] ‘The Cambridge Fortnightly' no.3 vol.1, 1888, cover by Roger Fry. [REF/4/4]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_25_1242x1920.jpg)

![First page of 'Some problems of phenomenology and its application to Greek art: a dissertation', Fry’s fellowship dissertation, 1891. [REF/1/13] First page of 'Some problems of phenomenology and its application to Greek art: a dissertation', Fry’s fellowship dissertation, 1891. [REF/1/13]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_26.jpg)

Bate's Art School and the N.E.A.C.

After graduating, it was agreed with his father, who had consulted the artist Briton Riviere and the family friend Herbert Marshall, that Fry should attend Francis Bate’s art school in the Applegarth Studio at Hammersmith. The teaching there was somewhat unconventional and far more focussed on the analysis of impressions than precise techniques with a pencil, perhaps due to Bates’ familiarity with French Impressionists. This training was not in a style favoured by the Royal Academy and Bates regularly exhibited with the New England Art Club (hereafter ‘N.E.A.C.’). Their ‘London Impressionists’ exhibition also included works by Whistler and Sickert, both of whom influenced Fry, although his tastes differed from theirs at times.

Fry’s parents moved to 1, Palace Houses, Bayswater, and Fry lived there after Cambridge. This cultural change led to some tension.

In 1891, his father paid for him to travel to Italy to see for himself what he’d learned from Middleton and the writings of Ruskin. Pip Hughes was his travel companion. Fry sketched while travelling and met artists like Giovanni Costa. He visited Rome, Sicily and Naples, then conducted a walking tour of Salerno, Amalfi and Sorrento, before settling in Florence. He then had another walking tour of Volterra, Prato, San Gimignano and Lucca, visiting Siena and Ravenna before finishing his trip in Venice.

While in Venice, he met the Widdrington family, of Newton Hall in Northumberland, forming a friendship with Idonea (Ida) Widdrington, which developed into romance. They were very different in character and when he proposed marriage, she responded “I love you too well to spoil your life, and I feel almost sure this would be the result.”

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 24 January 1889, giving his first impressions of Bates’ studio. [REF/3/46/2] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 24 January 1889, giving his first impressions of Bates’ studio. [REF/3/46/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_27.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 24 January 1889, giving his first impressions of Bates’ studio. [REF/3/46/2] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 24 January 1889, giving his first impressions of Bates’ studio. [REF/3/46/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_28.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 15 February 1891, regarding Pip Hughes and Rome. [REF/3/46/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 15 February 1891, regarding Pip Hughes and Rome. [REF/3/46/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_29.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 15 February 1891, regarding Pip Hughes and Rome. [REF/3/46/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 15 February 1891, regarding Pip Hughes and Rome. [REF/3/46/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_30.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_31.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_32.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_33.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Dickinson, 21 April 1891, regarding Florence. [REF/3/46/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_34.jpg)

Académie Julian

Fry returned to Bayswater and Bate’s studio. In 1891, he had two paintings exhibited at the N.E.A.C. The following year, his family moved to Failand, giving Fry a little more independence.

In January 1892, Fry went to the Académie Julian, a large private art school in Paris, where he studied under Benjamin Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens, and where William Rothenstein was a fellow student. It appears he didn’t settle in there, perhaps because the style of art taught there was very different to his and perhaps because Dickinson had accompanied him. Dickinson attended lectures during the day and they went to the theatre in the evenings.

Whatever the influence Paris had on him as an artist, it seems to have developed his appreciation of art and his abilities as a critic. He became familiar with ‘Neo-Impressionism’. He wrote a review of George Moore’s Modern Art for the Cambridge Review, which prompted Moore to suggest he write something for the Fortnightly Review. Fry wrote ‘The Philosophy of Impressionism’, which the editors did not accept. Francis Spalding says that if it had been accepted, it ‘would have earned Roger Fry a position among the most advanced writers on art in England’. He would have to wait for such an accolade.

![Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27] Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_35.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27] Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_36.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27] Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_37.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27] Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 21 February 1892, regarding Paris. [NW/2/27]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_38.jpg)

![Fry described his experiences in Paris in a lecture given in Bangor on 18 January 1927. [REF/1/117/2, typescript] Fry described his experiences in Paris in a lecture given in Bangor on 18 January 1927. [REF/1/117/2, typescript]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_39.jpg)

![Fry described his experiences in Paris in a lecture given in Bangor on 18 January 1927. [REF/1/117/2, typescript] Fry described his experiences in Paris in a lecture given in Bangor on 18 January 1927. [REF/1/117/2, typescript]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_40.jpg)

![Fry described his experiences in Paris in a lecture given in Bangor on 18 January 1927. [REF/1/117/2, typescript] Fry described his experiences in Paris in a lecture given in Bangor on 18 January 1927. [REF/1/117/2, typescript]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_41.jpg)

![First page of ‘The Philosophy of Impressionism’. [REF/1/58] First page of ‘The Philosophy of Impressionism’. [REF/1/58]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_42.jpg)

Move to Chelsea

In spring 1892, Fry moved in with Robert Trevelyan, his friend from Cambridge and fellow Apostle. Fry kept a small studio at 29 Beaufort St, Chelsea. This saw the start of a period of artistic experimentation, rather than tuition.

He took two trips to Blythborough, in Suffolk, painting and re-painting landscapes, sometimes approaching an almost Post-Impressionist style. Concerned that his paintings shouldn’t be too literal, he wished to avoid ‘imitation’.

An N.E.A.C. exhibition in 1892 brought Fry further recognition as an artist. He started painting portraits, including sitters like Cecilia Widdrington (who he became close to despite their age difference) and Edward Carpenter. The latter was exhibited at the N.E.A.C. in 1894 and considered a great success.

In 1893, he attended evening classes run by Sickert at The Vale, in Chelsea. He also met William Rothenstein that year.

![Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 3 November 1893, concerning his Suffolk paintings. [REF/3/57/28] Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 3 November 1893, concerning his Suffolk paintings. [REF/3/57/28]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_43.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 3 November 1893, concerning his Suffolk paintings. [REF/3/57/28] Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 3 November 1893, concerning his Suffolk paintings. [REF/3/57/28]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_44.jpg)

Cambridge Extension Movement

Fry became increasingly focused on Old Masters and in 1894 he began lecturing for the Cambridge Extension Movement, at Eastbourne and Brighton. He took two trips to the Siene, in 1894 with Alfred Thornton, and in 1895. Between those two trips, he visited Italy again, visiting Milan, Bologna, Florence and Bergamo, with A.M. Daniel (who later became Director of the National Gallery). Fry became more interested in expressive content. His painting ‘The Valley of the Seine’ was exhibited in the N.E.A.C. winter exhibition and bought by Trevelyan for £30.

The 1890s saw Fry turning some of his attention to design. He advised his father on the choice of stucco frieze for the Failand dining room, contributed drawings for Ashbee’s Whitechapel to Camelot (1892), designed bookplates for Alys and Bertrand Russell, furniture for McTaggart, curtains for Alys Russell and a drawing room frieze for the Trevelyans. In 1895, he created a wall painting on the chimney breast in the drawing room of Ashbee’s home, ‘Magpie and Stump’.

In autumn 1896, Fry curated an exhibition at the Bijou Theatre at Cambridge, exhibiting the works of young British artists.

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 26 June 1895. [REF/3/29] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 26 June 1895. [REF/3/29]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_45.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 26 June 1895. [REF/3/29] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 26 June 1895. [REF/3/29]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_46.jpg)

![Roger Fry’s wall painting in Ashbee’s home, ‘Magpie and Stump’. [CRA/23] Roger Fry’s wall painting in Ashbee’s home, ‘Magpie and Stump’. [CRA/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_47.jpg)

![Design for bookplate, for Bertrand Russel. [REF/4/5] Design for bookplate, for Bertrand Russel. [REF/4/5]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_48_1135x1920.jpg)

![First page of a letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, November/December 1896, describing the logistical challenges of his Cambridge exhibition. [REF/3/58/1] First page of a letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, November/December 1896, describing the logistical challenges of his Cambridge exhibition. [REF/3/58/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_49_1545x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, November/December 1896, describing the logistical challenges of his Cambridge exhibition. [REF/3/58/1] Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, November/December 1896, describing the logistical challenges of his Cambridge exhibition. [REF/3/58/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_50_1551x1920.jpg)

Helen Coombe

Helen Coombe was a painter and stained-glass window designer. She was born in Lee, Kent, on 23 March 1864, the eighth of twelve children of Joseph Coombe (a successful corn and flour merchant) and Laura Beaumont Coombe (née Russell). Her parents were English, but the family business had been conducted in Ireland. In 1881, when Helen was seventeen, she entered St John’s Wood Art Schools. The following December she was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools (RAS), where her achievements included winning a prize for the best drawing of a statue or a group. After leaving the RAS, she worked with several important figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement and pursued further studies at the National Art Training School.

Fry first saw Helen Coombe at his lodgings at 29 Beaufort Street on 27 May 1895. They were introduced by Trevelyan, who had initially intended to introduce her to Edward Marsh at 30 Bruton Street, off Berkeley Square, only to find Marsh (a fellow Apostle) was not at home. For Fry it was a case of love at first sight, but more than a year passed before Helen fell in love with him, her feelings eventually warmed by the advice he gave her when she was decorating Arnold Dolmetsch’s ‘Green’ harpsichord for display at the Arts and Crafts exhibition at the New Gallery in October 1896. They married on 3 December, at Great St Bartholomew’s in the City. Their honeymoon was an extended one, beginning in France and continuing in Algeria, Tunisia, and Sicily. Then they travelled through Italy, their main stops being in Naples, Rome, Florence, and Venice. They returned home in August 1897 by way of Switzerland and France. They had been away for eight months. Plans to settle down to work had to be abandoned in early September when Helen was diagnosed with lung trouble. On doctor’s advice, they went abroad for the winter. They chose to return to Italy for about six months, staying first in Ravello, then in Rome and Florence. They painted, studied and copied Italian art, and in Florence made the important acquaintance of Bernard Berenson.

In 1898, Fry gave a series of lectures on Venetian art for the Cambridge Extension Movement and was commissioned to write a ten thousand word monograph on Giovanni Bellini, for £25, by the Sign of the Unicorn publishers. Fry’s Giovanni Bellini was published in 1899. It included an acknowledgement of the influence and encouragement of Bernard Berenson, who had already discussed the notion of ‘tactile values’ in Venetian art.

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 1896, concerning his feelings for her. [REF/3/58] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 1896, concerning his feelings for her. [REF/3/58]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_51_2467x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 1896, concerning his feelings for her. [REF/3/58] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 1896, concerning his feelings for her. [REF/3/58]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_52_2460x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_53.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_54.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_55.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_56.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_57.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1896, concerning Helen Coombe. [REF/3/57/23]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_58.jpg)

Establishing his reputation as a critic

After the publication of Giovanni Bellini, Henry Newbolt (an old Cliftonian) asked Fry to write six articles on Italian art for the Monthly Review, a new periodical. With these, Fry’s scholarly reputation was established. He received further commissions but his personal life prevented them coming to fruition.

In the early summer of 1898, very soon after Fry and Helen had returned from Italy, she suffered what he described as a ‘nervous breakdown’. She was hospitalised for over six months. After her discharge, in December, she and Fry took up residence at Ivy Holt, Dorking. By summer 1899, she had recovered sufficiently to resume work as an artist, and in October-December she accompanied Fry on an art history tour of the Netherlands, Germany, and northern Italy.

In March 1901, their son Julian was born, and the following year they had a daughter, Pamela. Helen suffered from further mental ill-health in the autumn and winter of 1903-4.

In 1901, Fry wrote 47 pages on Italian art for MacMillan’s Guide to Italy. He also wrote two essays on Giotto, for the Monthly Review, which were later reprinted as Vision and Design (1920). Fry had become the art critic for Pilot and now took that role for the Atheneum too. He maintained a preference for classical art. This was reflected in his own painting and his comments as a member of the jury of the N.E.A.C.

In 1902, Fry visited Bruges with Helen, to see an exhibition of Flemish art. In the autumn, he went to Vicenza and Venice.

In 1903, Fry had his first solo exhibition, at the Carfax Gallery, where he displayed 24 watercolours and seven oil paintings. It was a great success. One of the paintings was bought by the fellow-Apostle Edward Marsh, who was becoming a serious collector and eventually became a major patron of the arts.

In the same year, Fry became a critic for the Burlington Magazine. Throughout editorial and financial difficulties, Fry had a significant positive influence on the magazine, although his views did raise tensions with the likes of Berenson.

Despite his reputation as an expert on art, Fry was rejected for the Slade Professorship of Fine Art in Cambridge, in June 1904. This may have been partly related to his criticism of such institutions as the Royal Academy and the National Gallery.

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1898, concerning Helen’s nervous breakdown. [REF/3/57/32] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1898, concerning Helen’s nervous breakdown. [REF/3/57/32]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_59_2434x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1898, concerning Helen’s nervous breakdown. [REF/3/57/32] Letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 1898, concerning Helen’s nervous breakdown. [REF/3/57/32]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_60_2456x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 9 June 1899, concerning art’s relationship with life and religion. [NW/2/27] Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 9 June 1899, concerning art’s relationship with life and religion. [NW/2/27]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_61.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 9 June 1899, concerning art’s relationship with life and religion. [NW/2/27] Letter from Roger Fry to Nathaniel Wedd, 9 June 1899, concerning art’s relationship with life and religion. [NW/2/27]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_62.jpg)

![Drawing by Roger Fry, 1902, after Giambono’s ‘Man of Sorrows’. [REF/4/1/24] Drawing by Roger Fry, 1902, after Giambono’s ‘Man of Sorrows’. [REF/4/1/24]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_63.jpg)

![Sketch by Roger Fry, 1902, of Bellini’s ‘Drunkenness of Noah’. [REF/4/1/24] Sketch by Roger Fry, 1902, of Bellini’s ‘Drunkenness of Noah’. [REF/4/1/24]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_64_2813x1920.jpg)

![Detail by Roger Fry, 1902, of the head of one of Noah’s sons in Bellini’s ‘Drunkenness of Noah’. [REF/4/1/24] Detail by Roger Fry, 1902, of the head of one of Noah’s sons in Bellini’s ‘Drunkenness of Noah’. [REF/4/1/24]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_65_2715x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 16 April 1906, discussing their early days at Ivy Holt. [REF/3/58/4] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 16 April 1906, discussing their early days at Ivy Holt. [REF/3/58/4]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_66_3033x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 16 April 1906, discussing their early days at Ivy Holt. [REF/3/58/4] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Coombe, 16 April 1906, discussing their early days at Ivy Holt. [REF/3/58/4]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_67_3028x1920.jpg)

New York

Facing considerable financial troubles, the Burlington’s future was in doubt and the magazine’s New York agent invited Fry to visit there to raise funds. Once there, he met various people associated with the Metropolitan Museum, including its President, J. Pierpont Morgan. Fry was offered the position of Assistant-Director, having offered the Directorship to Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke. Fry felt initial optimism about the art scene in New York, and hoped the position offered the flexibility for him to continue writing and lecturing, but negotiations about the terms of his appointment did not go well. Fry began to question Morgan’s character and interest in art. Fry returned to Britain without having gained the appointment.

To his surprise, he soon discovered that he was being considered for the Directorship of the National Gallery. Meanwhile, he wrote an introduction and notes for a new edition of Reynolds’ Discourses. During the spring of 1905, he travelled to Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Frankfurt and Berlin looking at Old Masters on the market but it isn’t clear who he was advising. That July, Pierpont Morgan sought his advice. By November he received a new offer from the Metropolitan Museum and in December the Museum announced his appointment as the Curator of Paintings, although he did not accept it until January 1906. Immediately after that, the Prime Minister offered him the Directorship of the National Gallery, which Fry felt duty bound to refuse, as he had prior commitments.

There was a distinct lack of clarity concerning the terms of his Curatorship at the Metropolitan Museum, not least in terms of how much of the year he must spent in New York. His priority was acquisition, which he considered from historical and aesthetic perspectives. In November 1906, he outlined what he felt was deficient in their existing collections and in the space of a year he acquired 54 new paintings, including works by Bellini, Lotto, Holbein, Blake, Renoir and Whistler. He rehung Gallery 24 by aesthetic interest, not historic period, paying close attention to the framing of the works and the decoration of the room. His cleaning of certain works was criticised by some but a report written by the Director and his Assistant for the trustees notes that the original paint was unaffected by the cleaning.

In April 1906, somewhat disillusioned with America, Fry returned to his wife and two children, at 22 Willow Road, Hampstead, where they had been living for over three years.

Vanessa Stephen (later Bell) first visited the Frys at this house, having seen them in the Fellows Garden at King’s College in 1902 or 1903.

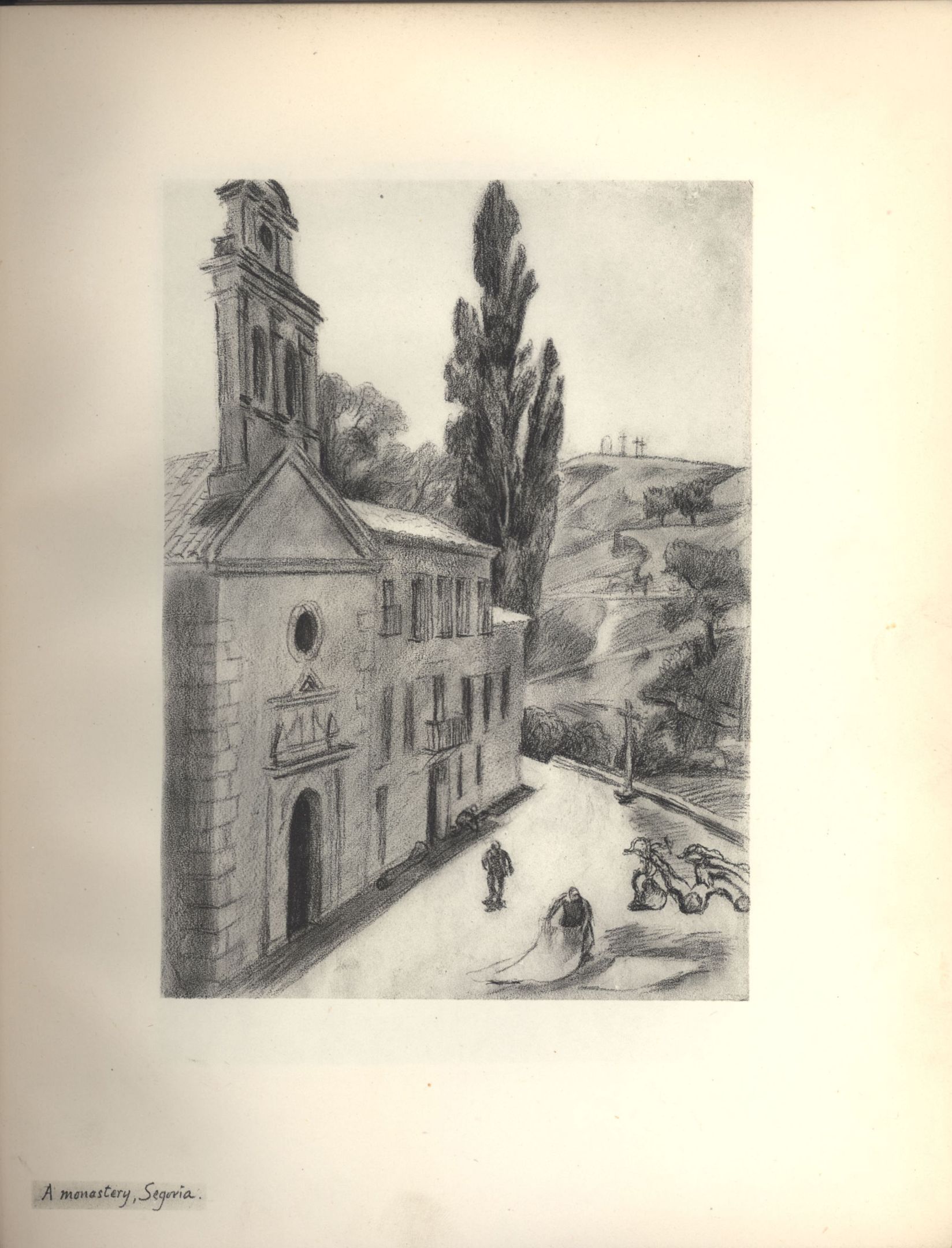

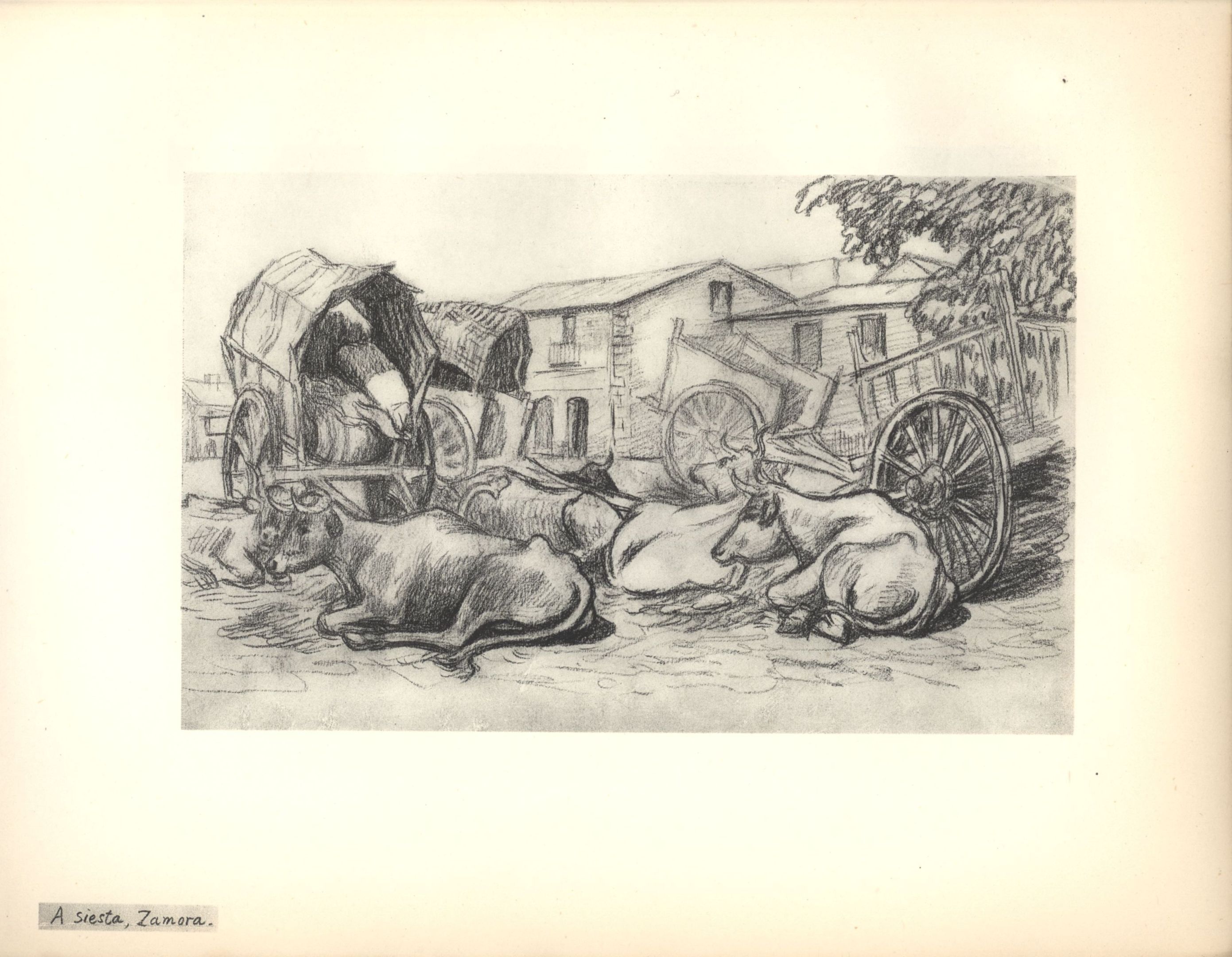

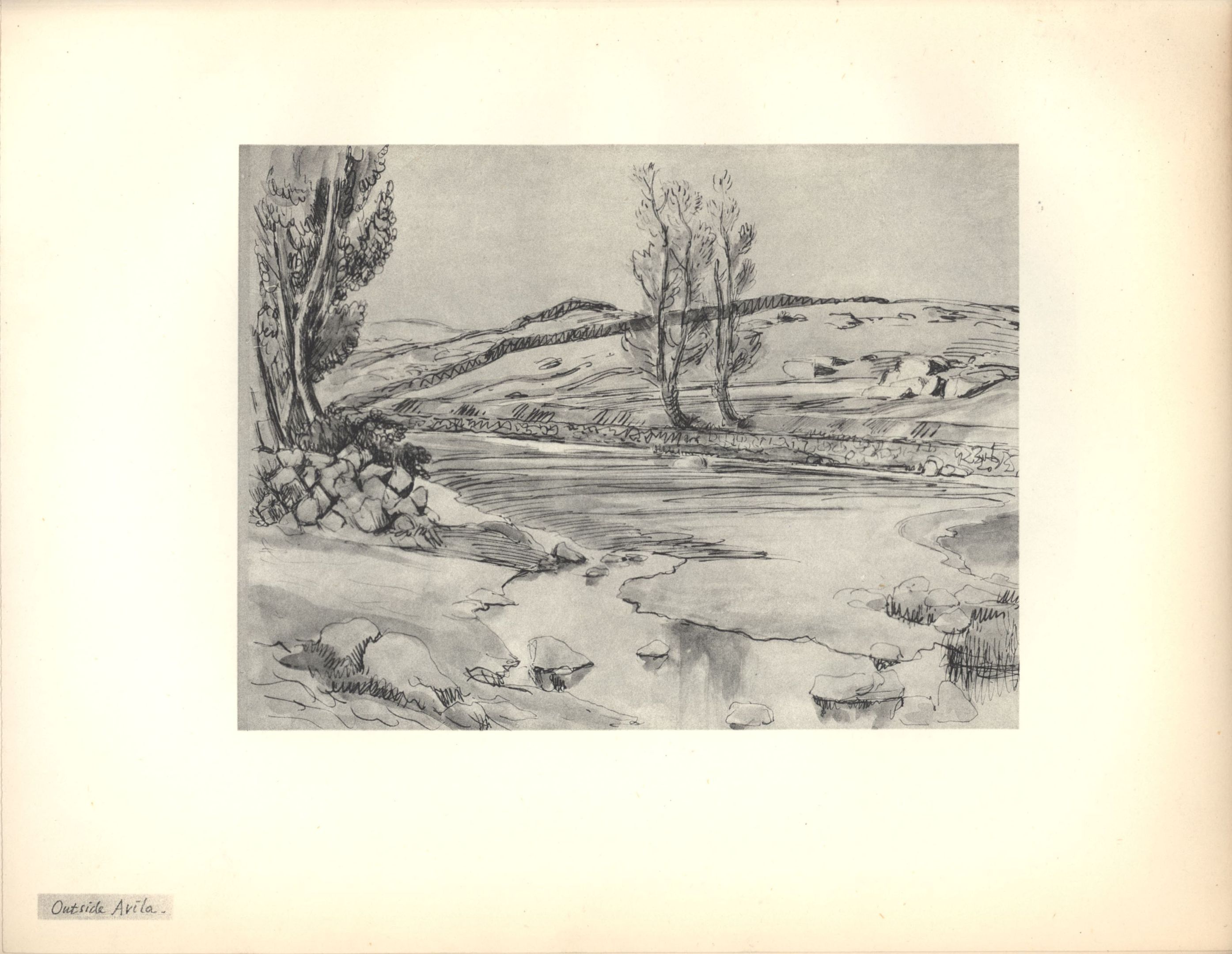

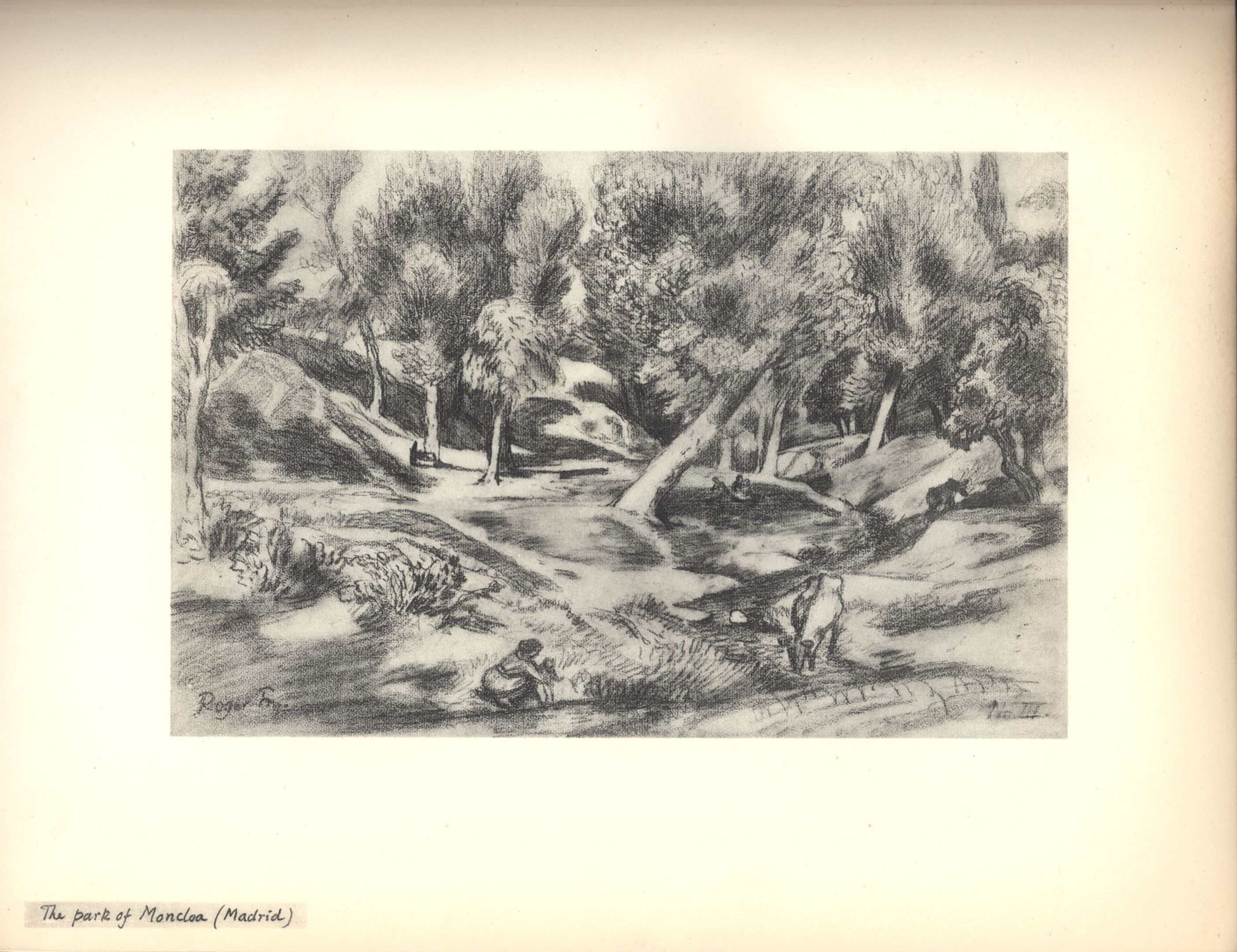

Fry travelled in France, Holland, Italy and Spain, selecting works for the Metropolitan and developing his own interest in Dutch Old Masters and Spanish art. He recommended the acquisition of work which weren’t to his own personal taste but in which he recognised the artist’s talents. He also bought or reattributed drawings.

In December 1906, Fry felt unable to continue in his role while supporting his wife through her ill-health, so he asked for his title to be changed to European Advisor. Morgan was reluctant to accept this. Tensions between the two had become worse, as Fry felt Morgan’s own art collecting presented a conflict of interest for the Metropolitan’s President. Fry had advised John C. Johnson on his private collection, and carried out restorations for him, but always put the needs of the Metropolitan Museum first. In 1907-1909, the Metropolitan changed its acquisition strategy, preferring fewer but more expensive purchases, allowing Fry to assist Johnson more. In the Metropolitan Museum’s Annual Report for 1907, the news was broken that Fry’s role had been changed to European Advisor to the Department of Paintings. That March, he met Morgan in Italy, where they visited exhibitions and private collections, seeking to acquire artworks. Fry’s relationship with the Metropolitan becoming more remote coincided with the deterioration of his wife’s mental health. She entered The Priory at Roehampton, under the care of Dr Chambers. In June 1909, Fry asked Kleinberger’s Gallery, in London, to set aside Fra Angelico’s ‘Virgin and Child’ for the Metropolitan, only to find that Morgan bought it for his private collection. Fry wrote a letter to Morgan, which only made tensions worse, then Herbert Horne questioned the attribution.

After they rejected two of Fry’s paintings for their Spring 1907 exhibition, he resigned from the N.E.A.C. the following year. That July, he shared an exhibition at the Alpine Club Gallery with the Hon. Neville Lytton.

Helen was hospitalised again for eight months in 1907-1908, and in November 1910 was admitted to The Retreat, York, never to emerge before her death in 1937.

In September 1909, Fry took on the joint-editorship of the Burlington Magazine, which only required two days a week and brought a salary of £150 per year, so Fry felt it would not affect his work for the Metropolitan. Although it is not clear how it ended, Fry’s relationship with the Metropolitan ceased the following February.

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 13 January 1905, expressing excitement about the New York art scene. [REF/3/58/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 13 January 1905, expressing excitement about the New York art scene. [REF/3/58/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_68.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 13 January 1905, expressing excitement about the New York art scene. [REF/3/58/3] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 13 January 1905, expressing excitement about the New York art scene. [REF/3/58/3]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_69.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, [1905], concerning J.P. Morgan. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, [1905], concerning J.P. Morgan. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_70_2426x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, [1905], concerning J.P. Morgan. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, [1905], concerning J.P. Morgan. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_71_2441x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 1906, concerning the offer from the National Gallery. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 1906, concerning the offer from the National Gallery. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_72_3013x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 1906, concerning the offer from the National Gallery. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 1906, concerning the offer from the National Gallery. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_73_2991x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 17 April 1906, describing his decoration and rehanging in the Museum. [REF/3/58/4] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 17 April 1906, describing his decoration and rehanging in the Museum. [REF/3/58/4]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_74_3025x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 17 April 1906, describing his decoration and rehanging in the Museum. [REF/3/58/4] Letter from Roger Fry to Helen Fry, 17 April 1906, describing his decoration and rehanging in the Museum. [REF/3/58/4]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_75_2994x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_76_2463x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_77_2424x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_78_2454x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35] Letter from Roger Fry to Lady Fry, 6 August 1907, concerning his title being changed to European Advisor and his increased recognition as an artist being unmatched by his enthusiasm. [REF/3/57/35]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_79_2434x1920.jpg)

![Untitled memoir of Italy, describing a day in May 1907 spent with Pierpont Morgan and entourage in Tuscany, Umbria and Le Marche collecting treasures for Morgan's personal collection. [REF/1/165] Untitled memoir of Italy, describing a day in May 1907 spent with Pierpont Morgan and entourage in Tuscany, Umbria and Le Marche collecting treasures for Morgan's personal collection. [REF/1/165]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_80_1482x1920.jpg)

Durbins

![Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 8 April 1908, concerning his plans for a house close to the Chantries at Guildford. [REF/3/57/36] Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 8 April 1908, concerning his plans for a house close to the Chantries at Guildford. [REF/3/57/36]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_81_2427x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 8 April 1908, concerning his plans for a house close to the Chantries at Guildford. [REF/3/57/36] Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 8 April 1908, concerning his plans for a house close to the Chantries at Guildford. [REF/3/57/36]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_82_2419x1920.jpg)

![Snapshot of Duncan Grant, Pamela and Julian Fry and Troth Swinburne sitting on the lawn at Durbins, 1910. [REF/6/8] Snapshot of Duncan Grant, Pamela and Julian Fry and Troth Swinburne sitting on the lawn at Durbins, 1910. [REF/6/8]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_83_3198x1920.jpg)

![Exterior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Exterior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_84.jpg)

![Exterior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Exterior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_85.jpg)

![Exterior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Exterior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_86_2564x1920.jpg)

![Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_87.jpg)

![Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_88.jpg)

![Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_89.jpg)

![Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9] Interior photograph of Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/9]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_90.jpg)

![Portrait of REF at Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/2] Portrait of REF at Durbins, taken by A.C. Cooper and Co., King St., London, 1913-19. [REF/6/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_91.jpg)

Aesthetics

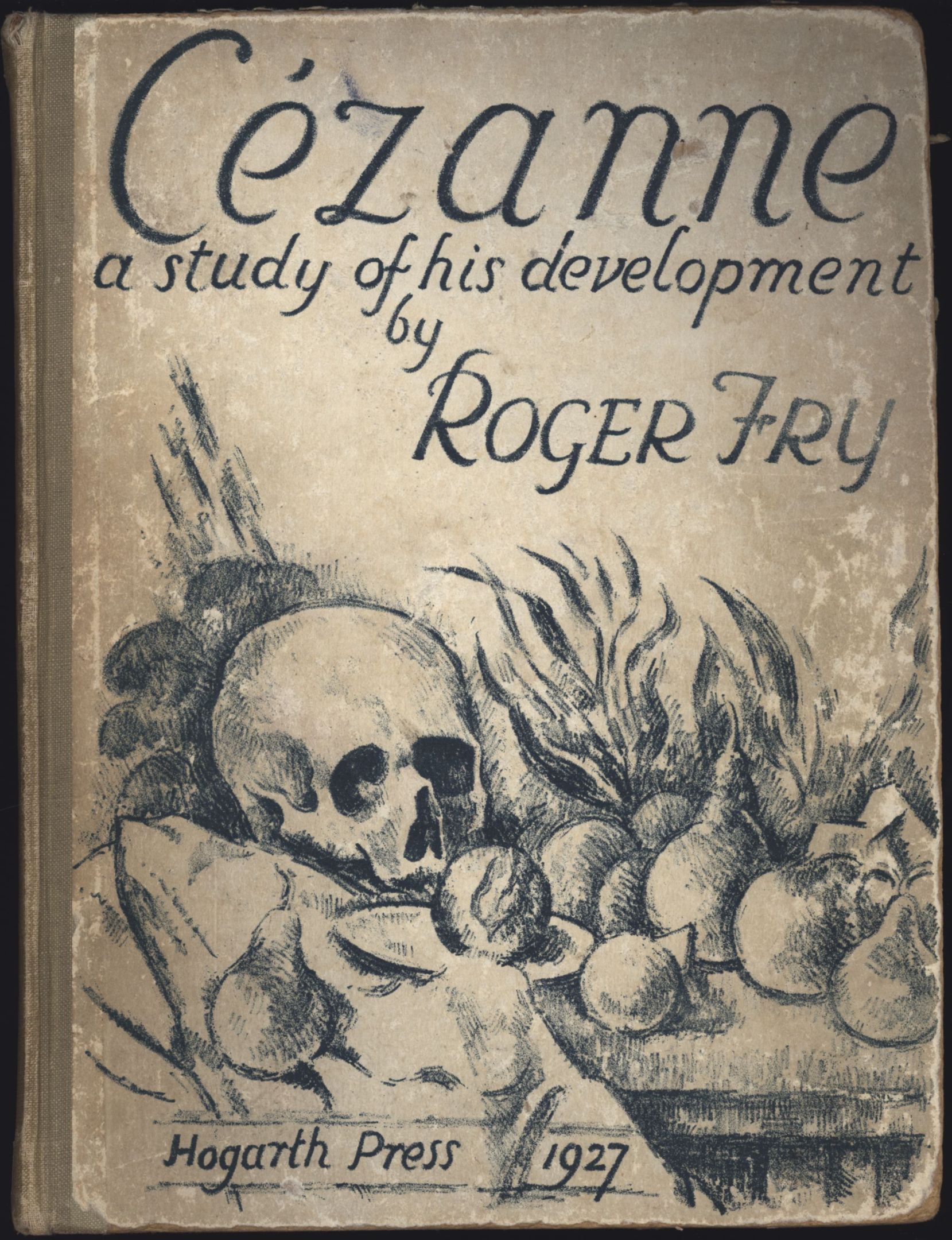

Since seeing a Chardin still life in an exhibition in 1902, Fry had begun to recognise the significance of form, not just representation, in one’s reaction to an artwork.

He had developed an appreciation of Cézanne, and in a letter to the Editor of the Burlington Magazine, March 1908, entitled ‘The Last Phase of Impressionism’, Fry wrote that ‘the first thing the Neo-Impressionist must do is to recover the long obliterated contour and to fill it with simple undifferentiated masses’.

In 1909, he delivered lectures in New York and London, in which he discussed Dramatic, Lyric, Comedic and Epic art. After that, Fry delivered a series of lectures on ‘The Language of Art’, which were very well received.

In April 1909, Fry had a one-man show at the Carfax Gallery, which, it has been suggested, did not demonstrate a connection between such theory and practice in his own works.

In 1909, he published ‘An Essay in Aesthetics’. As noted by Spalding, he was starting to move away from the subject of the ‘relationship between representation content and the formal qualities used to express it’. She describes it as a ‘rough diamond’, noting ‘It touches upon a number of problems peculiar to the subject, such as the relation of art to morality and the nature of aesthetic emotion, without pursuing any of these questions in depth.’

The following year, Fry’s position at the Metropolitan Museum was terminated. He applied for the Slade Professorship at Oxford but was unsuccessful. On top of these disappointments, Fry had to face the upset of his wife being committed.

![Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 14 February 1910, concerning his application for the Slade Professorship in Oxford. [REF/3/57/37] Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 14 February 1910, concerning his application for the Slade Professorship in Oxford. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_92_2450x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 14 February 1910, concerning his application for the Slade Professorship in Oxford. [REF/3/57/37] Letter from Roger Fry to his father, 14 February 1910, concerning his application for the Slade Professorship in Oxford. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_93_2458x1920.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 24 September 1910, concerning love and hurt. [REF/3/46/6] Letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 24 September 1910, concerning love and hurt. [REF/3/46/6]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_94.jpg)

![Letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 24 September 1910, concerning love and hurt. [REF/3/46/6] Letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 24 September 1910, concerning love and hurt. [REF/3/46/6]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_95.jpg)

Bloomsbury and Post-Impressionism

In January 1910, a chance encounter with Vanessa Bell and her husband Clive Bell, at Cambridge Station, allowed what had been a faint acquaintance to develop into a friendship and they were later to visit him at Durbins. Fry being both an artist and a critic, he shared these common interests with Vanessa and Clive respectively, despite Fry being slightly older than them. Their worlds combined and he was introduced to Vanessa Bell’s Friday Club, which included Slade-trained painters. He first addressed the club on 21 February 1910. He was drawn into the Bloomsbury Group. Fry was spending two or three days in London, and the rest of the week in Durbins, where his sister Joan and staff looked after the house and children.

During the train journey Fry shared with the Bells, he told them of an idea for an exhibition on modern French artists. That October, it was mooted that the exhibition could take place in the Grafton Galleries the following January. Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy (the exhibition secretary) went to Paris to see art dealers and private collectors about artworks they might include in the exhibition. Fry had great success in Paris, after which MacCarthy visited Holland and Munich, where the work he got included a number of Van Goghs. He also wrote to C.J. Holmes, inviting him to join the exhibition committee. The exhibition, entitled ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ was opened on 8 November 1910 and ran until 15 January 1911. The exhibition included works by Manet, Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Matisse. Individual works by these artists had been displayed to little effect in British galleries before, but never in this way. The exhibition shocked the art world and received bad reviews in the press.

![Cover of John Maynard Keynes' copy of the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue, marked 'Under Revision'. [JMK/PP/70/1] Cover of John Maynard Keynes' copy of the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue, marked 'Under Revision'. [JMK/PP/70/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_96.jpg)

![Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1] Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_97.jpg)

![Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1] Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_98.jpg)

![Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1] Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_99.jpg)

![Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1] Preface to the ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/1]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_100.jpg)

![First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37] First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_101_1215x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37] Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_102_1205x1920.jpg)

![Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37] Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_103_1205x1920.jpg)

![Fourth page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37] Fourth page of a letter from Roger Fry to his father, 24 November 1910, concerning the press’ reaction to the exhibition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_104_1201x1920.jpg)

Turkey

The ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition greatly influenced the work of Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, the Bloomsbury artists. Shortly after it closed, Fry was offered the Directorship of the Tate Gallery but refused it.

Fry soon developed a short-lived romance with Lady Ottoline Morrell, who already knew of Post-Impressionist artists, had been on the Post-Impressionist exhibition committee and had got on well with Helen Fry. She had joined Fry et al in Paris when selecting works for the exhibition. The relationship ended when he went with the Bells, and H.T.J. Norton to Turkey, to see the Byzantine mosaics. They visited Istanbul and Bursa. They sketched and painted, but the trip took a tragic turn when Vanessa Bell suffered a miscarriage. He helped nurse her. Virginia, her sister, joined them afterwards, for the trip home. On their return, Fry fell out with Lady Ottoline. In July, Vanessa spent some time convalescing at Millmead Cottage in Guildford, where she and Fry spent much time together. Fry had various visitors to Durbins that summer, not least his fellow Bloomsbury artists. The group spent that September in Studland Bay.

Fry became increasingly influenced by Matisse, as well as the Turkish mosaics he had seen, experimenting in new techniques in his 1911 paintings of subjects such as Turkish landscapes and Studland Bay. Spalding likens the influence of mosaics on Bloomsbury art to stained glass and Vanessa Bell wrote to Fry describing it as not ‘painting in spots but considering the picture as patches.’

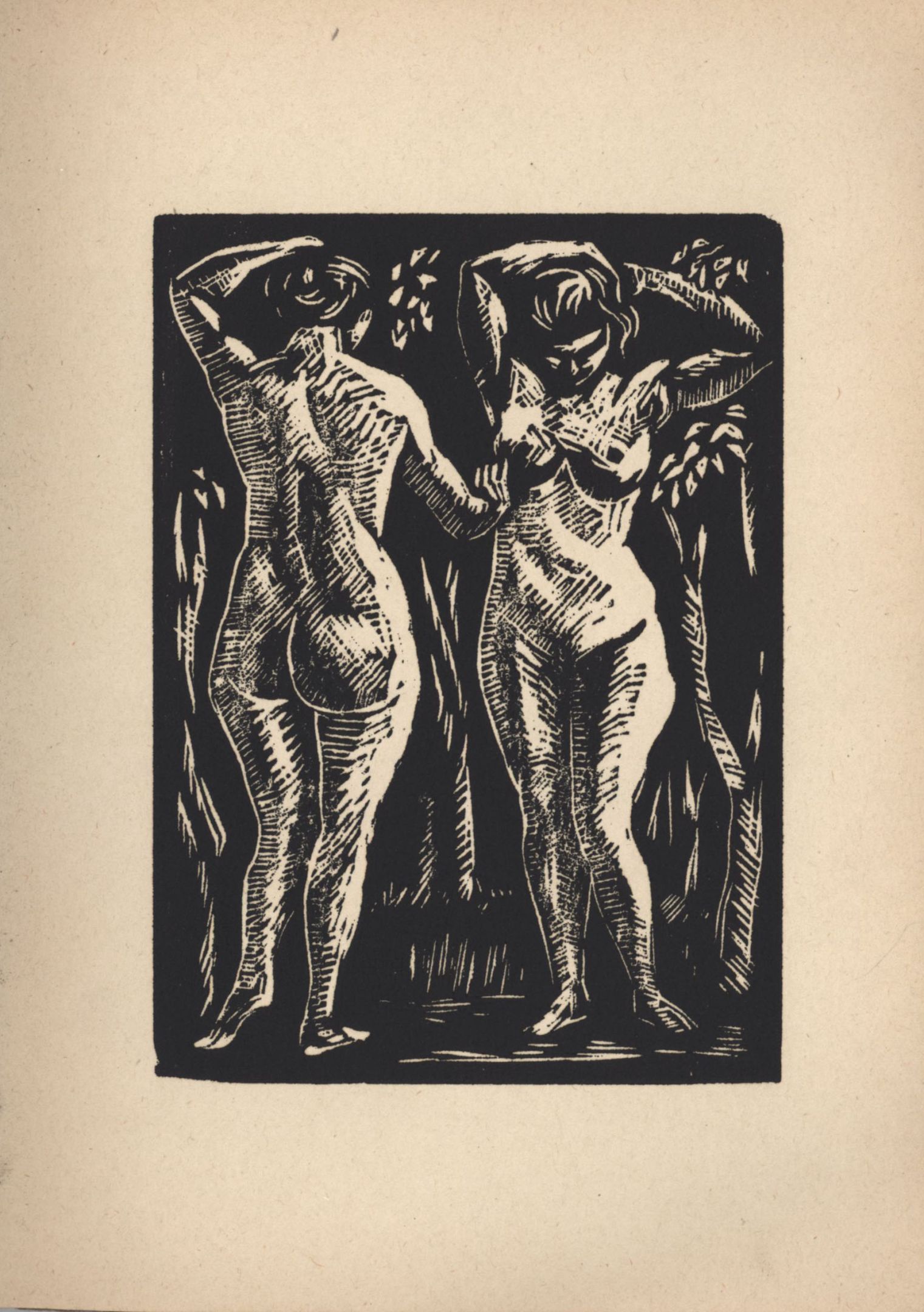

In the summer of 1911, Fry was invited to decorate the dining hall at the Borough Polytechnic. Fry invited Duncan Grant, Frederick Etchells, Bernard Adencey, Macdonald Gill and Albert Rothenstein to paint panels on the theme ‘London on Holiday’. Spalding notes that some of the panels were greatly influenced by Byzantine art, not least Grant’s ‘Bathers’, which is now in the Tate’s collection.

That autumn, Fry, Duncan Grant and Clive Bell went to France and saw an exhibition of Cubism, which introduced Fry to a different form of ‘geometrical simplification and classification of natural form’. This influence can be seen in his portrait of E.M. Forster, which hangs in King’s College.

In January 1912, Fry held a one-man show at the Alpine Club Gallery, featuring fifty-two of his works.

![First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 6 February 1911, concerning his refusal of the Directorship of the Tate Gallery. [REF/3/57/37] First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 6 February 1911, concerning his refusal of the Directorship of the Tate Gallery. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_105_1222x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 6 February 1911, concerning his refusal of the Directorship of the Tate Gallery. [REF/3/57/37] Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 6 February 1911, concerning his refusal of the Directorship of the Tate Gallery. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_106_1214x1920.jpg)

Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition

The Grafton Galleries asked Fry to curate exhibitions each autumn. There was no such exhibition in 1911, as he failed to find the support of artists like William Rothenstein whom he wished to display next to works by younger English artists.

In July 1912 he visited Paris again, in search of artworks for his ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’. He also asked Boris Anrep to visit Russia in search of contemporary Russian art. Clive Bell selected English artworks for the exhibition. Important artists whose work was shown included Cézanne, Picasso and Matisse, culminating with Matisse’s ‘The Dance’. Fry showed a work by Douanier Rousseau for the first time in England and Russian prints adorned the staircases.

Chatto and Windus asked Fry to write a book on Post-Impressionism but he was too busy setting up the Omega Workshops, so recommended Clive Bell. As a result, Bell’s Art was published, marking a milestone in the discussion of aesthetics and ‘significant form’. Fry had already used the term ‘significant form’ but he and Bell did not always agree on the finer details of the theory.

Around this time, Vanessa Bell became less affectionate towards him, turning her affection back to her husband and also to Duncan Grant. Despite the success of his Post-Impressionist exhibitions, Fry began to feel frustrated about his career.

![End of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 June 1912, mentioning the British public’s attitude towards art. [REF/3/57/37] End of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 June 1912, mentioning the British public’s attitude towards art. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_107_1186x1920.jpg)

![First page of the Introduction to the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] First page of the Introduction to the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_108.jpg)

![Second page of the Introduction to the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] Second page of the Introduction to the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_109.jpg)

![First page of the French Group in the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] First page of the French Group in the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_110.jpg)

![Second and third pages of the French Group in the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] Second and third pages of the French Group in the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_111.jpg)

![Final pages of the French Group in the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] Final pages of the French Group in the ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_112.jpg)

![First page of a letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 18 February 1913, concerning the genesis of a theory on ‘significant form’ and a ‘scheme’ which would become the Omega Workshops. [REF/3/46/6] First page of a letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 18 February 1913, concerning the genesis of a theory on ‘significant form’ and a ‘scheme’ which would become the Omega Workshops. [REF/3/46/6]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_113_1614x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 18 February 1913, concerning the genesis of a theory on ‘significant form’ and a ‘scheme’ which would become the Omega Workshops. [REF/3/46/6] Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 18 February 1913, concerning the genesis of a theory on ‘significant form’ and a ‘scheme’ which would become the Omega Workshops. [REF/3/46/6]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_114_1622x1920.jpg)

![First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37] First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_115_1198x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37] Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_116_1193x1920.jpg)

![Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37] Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_117_1200x1920.jpg)

![Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37] Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 28 March 1913, concerning failure and ambition. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_118_1196x1920.jpg)

Omega Workshops

In the summer of 1911, after Fry, Henri Doucet and Duncan Grant all met to paint Fry’s daughter Pamela, he formed the idea of setting up the Omega Workshops. This would give artists a steady income by allowing them to work three mornings a week and earn thirty shillings in return. He felt this secure income would enable greater artistic creativity. By December 1912, he had formalised his idea for the Omega Workshops. Spalding notes that the name derives from Omega being the last letter in the Greek alphabet and implies ‘the last word’ in fashion.

Fry set about raising £2000 from patrons, assuming annual running costs of £600-£700. He intended the workshop to create wall decorations, painted silks for curtains and dresses, painted screens and furniture etc. The Omega Workshops were established in April 1913, at 33 Fitzroy Square. There he had ample space for cellar storage, showrooms and workshops. The company was officially registered in May 1913. Fry, Duncan grant and Vanessa Bell were its directors. Prior to registration, their fabrics appeared alongside paintings in the Grafton Group’s first exhibition.

The official opening of the Omega Workshops was on 8 July 1913. Those who attended the press and private view would have seen an eclectic mix of decorative items. There were few rules governing their designs and both the objects and the designs were kept anonymous, rather than being signed/stamped with the artist’s name. The Omega stamp was all that was used.

Artists associated with the Omega Workshops included Gaudier-Brzeska, Frederick Etchells and Wyndham Lewis, to name but a few. Struggles faced by the Omega included a falling-out between Fry and Wyndham Lewis, culminating in a ‘round robin’ letter, which Fry considered to be of an ‘entirely imaginary nature’. Nonetheless, Wyndham Lewis, Etchells, Hamilton and Wadsworth left the Omega Workshops. Roberts and Gaudier-Brzeska left to serve in the War. Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell withdrew in 1916, as Grant’s conscientious objection led them to go to Wissett Lodge in Suffolk. Fry, Nina Hamnett and Ronald Kristian remained.

When his uncle Joseph, who ran J.S. Fry and Sons, the chocolate firm, passed away, he left Roger Fry sufficient money to be sure of £1000 per year. This may have helped him, but nonetheless, the Omega Workshop faced financial struggles. They received a few significant commissions but their lack of advertising may have limited their business. Fry appears to have made the decision to close the Omega Workshop on 20 June 1919 and a clearance sale was held from 23 June until 9 July.

![Part of a letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 31 May 1913, concerning the Omega Workshops. [REF/3/46/6] Part of a letter from Roger Fry to Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, 31 May 1913, concerning the Omega Workshops. [REF/3/46/6]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_119_2186x1920.jpg)

![First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37] First page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_120_1214x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37] Second page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_121_1190x1920.jpg)

![Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37] Third page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_122_1201x1920.jpg)

![Fourth page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37] Fourth page of a letter from Roger Fry to his mother, 14 June 1913, concerning his hopes for the Omega Workshops and their influence on art in England. [REF/3/57/37]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_123_1181x1920.jpg)

![First page of a round robin signed by Etchells, Hamilton, Wadsworth and Lewis on their dispute with REF, c. October 1913. [REF/3/92] By permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity). First page of a round robin signed by Etchells, Hamilton, Wadsworth and Lewis on their dispute with REF, c. October 1913. [REF/3/92] By permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity).](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_124_1525x1920.jpg)

![Second page of a round robin signed by Etchells, Hamilton, Wadsworth and Lewis on their dispute with REF, c. October 1913. [REF/3/92] By permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity). Second page of a round robin signed by Etchells, Hamilton, Wadsworth and Lewis on their dispute with REF, c. October 1913. [REF/3/92] By permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity).](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_125_1540x1920.jpg)

![Third page of a round robin signed by Etchells, Hamilton, Wadsworth and Lewis on their dispute with REF, c. October 1913. [REF/3/92] By permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity). Third page of a round robin signed by Etchells, Hamilton, Wadsworth and Lewis on their dispute with REF, c. October 1913. [REF/3/92] By permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity).](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_126_1535x1920.jpg)

![First page of the Preface to ‘Copies and Translations (by English painters - Fry, Grant, Bell - of paintings by the masters)’, Omega Workshops exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] First page of the Preface to ‘Copies and Translations (by English painters - Fry, Grant, Bell - of paintings by the masters)’, Omega Workshops exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_127_1216x1920.jpg)

![Second page of the Preface to ‘Copies and Translations (by English painters - Fry, Grant, Bell - of paintings by the masters)’, Omega Workshops exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] Second page of the Preface to ‘Copies and Translations (by English painters - Fry, Grant, Bell - of paintings by the masters)’, Omega Workshops exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_128_1219x1920.jpg)

![‘Copies and Translations (by English painters - Fry, Grant, Bell - of paintings by the masters)’, Omega Workshops exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2] ‘Copies and Translations (by English painters - Fry, Grant, Bell - of paintings by the masters)’, Omega Workshops exhibition catalogue. [JMK/PP/70/2]](https://mediadepot.fra1.digitaloceanspaces.com/kingscamapps/s3fs-public/web-images/ARCHIVES_2025/Roger%20Eliot%20Fry%20%282%29/roger_129_1225x1920.jpg)

The War

Other members of the Bloomsbury Group became conscientious objectors but Roger Fry was too old to face conscription during World War One. In the spring of 1915, he visited his sister Margery who was working for the Quaker War Victims’ Relief Fund in the districts of the Marne and the Meuse. He assisted for a short while, before exploring the region on a bike. Breaking the journey with a visit to Paris and Cassis, he then went South to stay with Simon and Dorothy Bussy, at Roquebrune. While at La Souco, their home, he painted (influenced by Jan Vanden Eeckhoudt), and developed a friendship with Pippa Strachey.

In November 1915, Fry had a one-man show at the Alpine Club Gallery, where he exhibited fifty-four recent paintings. He also showed some Omega pottery.