History of the Chapel

King’s College Chapel is the oldest surviving building within the College site and perhaps the most iconic building in Cambridge. Work on this Chapel only started five years after King’s College was founded by Henry VI in 1441.

The Kings behind the building of the Chapel

Henry VI, the royal saint

Henry was only 19 when he laid the first stone of the 'College roial of Oure Lady and Seynt Nicholas' in Cambridge on Passion Sunday, 1441. At the time this marsh town was still a port so, to make way for his college, Henry exercised a form of compulsory purchase in the centre of medieval Cambridge, levelling houses, shops, lanes and wharves, and even a church between the river and the high street (now King's Parade). It took three years to purchase and clear the land.

Initially King's was to have a Provost and 12 impoverished students (the number of the apostles) but after work had begun on the Old Court, Henry decided on a much grander plan.

He now intended King's to have 70 scholars (representing the 70 early evangelists chosen by Jesus) drawn exclusively from the king's other foundation at Eton. For over 400 years King's College admitted only Etonians and claimed the privilege that its students should receive degrees without being examined.

Henry drew up detailed instructions for Eton and King's, and at both places his first concern was the chapel. He went to great lengths to ensure that King's College Chapel would be without equal in size and beauty.

No other college had a chapel built on such a scale: in fact, the building was modelled on the plan of a cathedral choir, the architect being Henry VI's master mason, Reginald Ely.

The foundation stone of the Chapel was laid on the feast of St James, 25 July 1446, by the king; it was the first step in his plan for a great court, of which the Chapel was to form the north side. Henry explained everything in his 'wille and entent' of 1448, but only the Chapel was ever completed.

The Yorkist Kings – Royal Murderers?

In 1455 the Wars of the Roses broke out when Richard Duke of York challenged Henry's right to the throne. The subsequent story of the building of the Chapel and the Wars of the Roses are closely intertwined. For the first 11 years of unrest, building continued under Henry's patronage, even though the annual grant of £1000 from the king's family estates, the Duchy of Lancaster, became irregular and then ceased altogether. Then, in 1461, Henry was taken prisoner.

On hearing the news the workmen packed up and went home; a half-cut stone, it is said, lay where they left it and was eventually used as a foundation stone for the neighbouring Gibbs building in 1724.

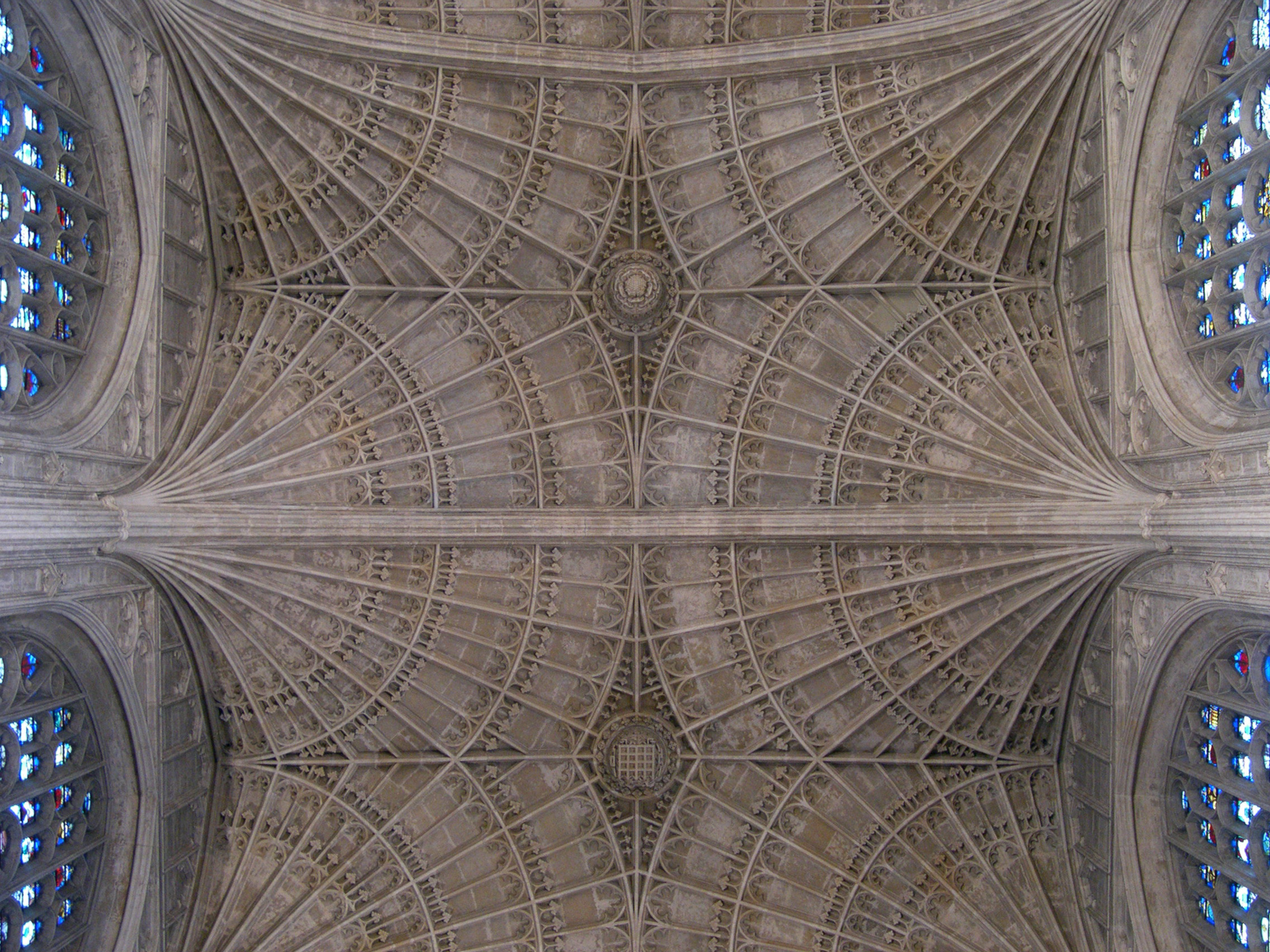

After 15 years of building, the foundations of the Chapel had been laid and the walls rose irregularly from east to west. A white magnesian limestone, from quarries at Tadcaster which belonged to the College, was used for much of this early phase and the upper limit of this, most clearly discernible in the buttresses (see photo below), marks approximately the level the building had reached by 1461.

Henry was murdered in the Tower of London on 21 May 1471. He had inherited two great kingdoms (England and France) from his father, and lost them both. He had, however, founded two of England's greatest colleges.

The new king, Edward IV, passed on to the College a little of the money that Henry had intended for his Chapel, but very little building was done in the 22 years between Henry's imprisonment and the death of Edward IV in 1483.

Work began again through the generosity of Richard III, who was later to be popularly depicted as a sinister hunchback. Richard gave instructions that 'the building should go on with all possible despatch' and to 'press workmen and all possible hands, provide materials and imprison anyone who opposed or delayed'. By the end of his reign the first six bays of the Chapel had reached full height and the first five bays, roofed with oak and lead, were in use.

Henry VII and Henry VIII – The Tudor Dynasty

It was left to the Tudor kings, Henry VII and Henry VIII, to achieve the final, spectacular completion to the Chapel.

Henry VII defeated and killed Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Initially he was preoccupied with bringing the country under control, and building work on the Chapel virtually ceased for another 2 years, despite the College's petition to the new king that 'the structure magnificently begun by royal munificence now stands shamefully abandoned to the sight'. Then, in 1506, Henry VII came to Cambridge and the St George's Eve service of the Knights of the Garter was held in the first five bays of the Chapel, which had a timber roof but no stone ceiling vaults. The open end was boarded up and decorated with the coats of arms of the Knights of the Garter painted on paper.

Henry VII's mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, had pledged herself to carry through the various pious projects begun by Henry VI and, prompted by her, Henry shrewdly perceived that his new dynasty needed the authority which 'the royal saint', Henry VI, could give. He decided to finish the Chapel that his uncle had begun, and sent some of the money to pay for it in the chest which can still be seen in the Chapel.

In 1508 work began again on a grand scale, and although Henry VII died in 1509 the terms of his will ensured that money was provided to 'perfourme and end al the warkes that is not yet doon in the said chirche'.

By 1512 the shell was finished and roofed throughout its length in timber and lead. Henry VII's executors gave a further £5000 to pay for vaulting the Chapel, and by 1515 the main structure was complete. This work, and most of the glazing of the windows, was done during the reign of his son, Henry VIII, who was responsible for the screen and much of the Chapel woodwork.

When Henry VIII died in 1547, just over a hundred years after the laying of the foundation stone, King's College Chapel was recognised as one of Europe's finest, late medieval buildings. It was in truth 'a work of kings'.

From the 17th to the 21st centuries

Henry VI's designs for a 'Great Court' were never carried out and for nearly 200 years there was little more than the Old Court for the everyday life of the College.

In the early 18th century a new plan for a great court was drawn up but only the Fellows' building, designed by James Gibbs, was built. Another hundred years was to pass before the court was completed by the building of the William Wilkin's Gothic pinnacled gatehouse and stone screen, dining hall and library and what is now called the Old Lodge, in 1824-28. The fountain (1874-1879), with a statue of the College's saintly Founder, stands in the centre of the Front Court. In 1829 Old Court, the original buildings of King's College, were sold and became part of the University's Old Schools.

The rood, a crucifix upon the screen, and a high altar in the Choir, for example, were all removed under Edward VI, restored under Mary, modified under Elizabeth, elaborated under Archbishop Laud, and removed again under Oliver Cromwell. Similarly, in the turbulent 17th century Benjamin Whichcote's sermons were a model of moderate and liberal churchmanship; he believed in tolerating differing opinions and characteristically insisted on half his stipend going to his banished predecessor.

The windows miraculously and mysteriously escaped the ravages of the Civil War, although one royalist observer claimed that, in inclement weather, the Chapel was used as a parade ground by Cromwell's troops: 'nor was it any whit strange to find whole bands of soldiers training and exercising in the royal Chapel of King Henry the Sixth'. (Querela Cantabrigiensis). The reforms of the 1860s brought about changes to college life, the most obvious being the admission of non-Etonians to the College in 1873 and, in keeping with the College's tradition of religious tolerance, there was an influx of Nonconformist students which may well have helped to consolidate the liberal traditions of King's.

The College grew rapidly, both in terms of student numbers and buildings, and by the beginning of the 20th century there had been a marked improvement in the quality of education which enhanced the College's academic standing.

The patrician habits of the old King's were beginning to die out: to be eligible for a college stipend (or dividend) Fellows had to live in Cambridge, and the Dean no longer rode to hounds direct from the Chapel.

Once again King's College Chapel escaped unscathed during the Second World War, when the glass of most of the windows was removed for safety. The opportunity was taken to clean, repair and photograph it. Only the West Window remained in place, appreciated at last in the absence of unfair competition.

The Chapel today