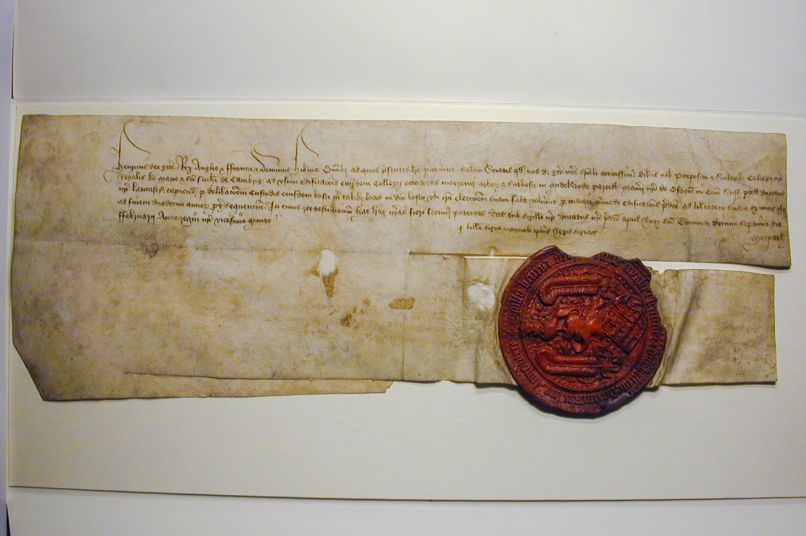

Archives

Introduction to the Archives Centre

The Archive Centre holds two types of documents:

The College Archives - the College's internal administrative records, and the Modern Archives - the personal papers of former members and associated individuals.

The Modern Archives are particularly strong in collections related to the Bloomsbury Group and the economists in Cambridge associated with John Maynard Keynes (KC 1902).

The College also has the largest known collection of Alan Turing's papers, which can be viewed online.

Explore the Archives

Contact the Archives

Archives Centre

King's College

King's Parade

Cambridge CB2 1ST

Tel: +44 (0)1223 331444

King's College

King's Parade

Cambridge CB2 1ST

Tel: +44 (0)1223 331444