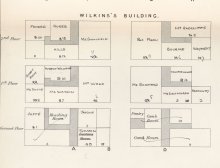

![Some of Forster 's undergraduate years were spent in lodgings not owned by King's at the time (as shown here). In his second year he lived in Bodley's, W7. [EMF/27/225] Some of Forster 's undergraduate years were spent in lodgings not owned by King's at the time (as shown here). In his second year he lived in Bodley's, W7. [EMF/27/225]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/emf-27-0225.jpg)

Edward Morgan Forster (1879-1970, KC 1897-1901 and 1945-1970) came up to King's in 1897 and read Classics, getting his BA in 1900. He spent a fourth year at King’s reading History. An inheritance from his great-aunt Marianne Thornton and the success of his novels made his adult life comfortably well off, but when in 1945 he lost the copyhold on a house inherited from his aunt Laura and in which he had lived for many years, he returned to King's an Honorary Fellow. From 1953 he resided at King's College with few responsibilities except those informal ones of the bachelor don, a figure that was fast becoming extinct in Cambridge.

This exhibition traces the influences that Forster and King's had on each other. It is written for those with a particular interest in King's, and is complementary to the broader-ranging Forster exhibition in the Archive Centre's regular series of on-line exhibitions.

![Forster; detail from 'King’s third years 1900' [EMF/27/224] Forster; detail from 'King’s third years 1900' [EMF/27/224]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/emf-27-0224a_emf.jpg)

The 141-year-old fountain in the Front Court is a few months younger than Forster himself. The photographs of the Front Court and Bodley's (Forster lived in W7 his second year) are much as Forster would have known them as a student.

The young Forster is shown below in his final year photo at Tonbridge (1897), and at right from a photograph of his cohort as 3rd years. The latter also shows Hugh Owen Meredith (known as HOM), Forster's young love, seated next to ghost story writer and future Provost M.R. James, their Senior Tutor. HOM is said to have inspired the character George in A Room with a View.

![HOM's proposal of Forster to the Apostles [KCAS/39/1/13_1901-02-02] HOM's proposal of Forster to the Apostles [KCAS/39/1/13_1901-02-02]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/kcas-39-1-13_1901-02-02_crop.jpg)

The undergraduate Forster was proposed by Hugh Meredith, and duly elected, to the secret University debating society known as The Apostles. The influence of their erudite discussions including issues of ethics, beauty and truth can be seen particularly in his later, nonfiction writing. Though he graduated soon after election he continued his association with the Society, attending meetings and occasionally giving papers such as A Roman "Society", the first page of which is shown below.

Forster's tutor Oscar Browning was a fellow Apostle, as were his other tutor Nathaniel Wedd and his mentor Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, about both of whom more below.

The list of attendees at the annual Apostles dinner in June 1910 lists other influential King's graduates who maintained their association with the Apostles (e.g. art critic Roger Fry and economist Maynard Keynes), and undergraduate poet Rupert Brooke who was for a time Secretary of the Society. Forster wrote to Brooke in October 1910 about delivering a paper, and in November 1911 that he was going to 'put all that I can remember of your paper on art into a novel'. Precisely which novel that might have been is not clear.

![Nathaniel Wedd (1864-1940), a few years before Forster came up. [EMF/27/227] Nathaniel Wedd (1864-1940), a few years before Forster came up. [EMF/27/227]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/emf-27-0227.jpg)

Forster's literary ambitions were encouraged at King’s by his first Tutor Nathaniel Wedd. In his memoir 'My books and I' Forster recalls 'Wedd had already helped me by remarking in a lecture that we all know more than we think. A cry of relief and endorsement arose from my mind, tortured so long by being told that it knows less than it pretended to know.' An annotation on the Tonbridge group photograph by a much older Forster reads: 'Mr Watson, who doubted my word in the 90s' indicating just how sensitive Forster was to encouragement or discouragement.

Several letters from Forster to Wedd survive; excerpts are shown below. They include one written in December 1901 in Florence where he tells of remembering that Wedd calling the Fra Angelicos 'almost too good' and going instead to see the 'Spring in the Academy (Roger Fry used to lick dirt off the Primavera when the custodian wasn't looking)', finishing with mention of mutual friends: 'It's a pity Meredith can't get away for Xmas. I have just had a letter from Dent, who is my chief Cambridge correspondent'. More on Dent below. Forster also seems to answer a question Wedd had asked, with 'As to writing, I have done none since the summer'.

![Edward Dent (1876-1957) about the time Forster was writing to him from Italy. [EMF/27/234] Edward Dent (1876-1957) about the time Forster was writing to him from Italy. [EMF/27/234]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/emf-27-0234.jpg)

Musicologist Edward Dent inspired at least one character in a Forster novel, advised Forster before he and his mother visited Italy beginning in 1901, and shared with Forster an interest in music.

In October 1901 Forster wrote to Dent that at Florence he and his mother would 'go to the hotel you told us of for a night, and then settle on a Pension.' Three days later, 'We have been here three days, and are very comfortable, but my mother hankers after an Arno view and a South aspect, so we are not stopping.' Compare that with the opening chapter of A Room with a View, in which Lucy and Charlotte do not have the view they were promised.

In May 1903 Forster wrote about when they disobeyed Dent’s advice about where to stay, with the result that some objectionable insect was discovered. Forster reported to Dent: 'Our gratitude + admiration for the extent + accuracy of your knowledge have always been immense, but now they are mingled with awe. We speak of you in the words of the hymn: “and soon the people all were dead who did not do as he had said.” '

There were many men at King’s during Forster's time whose only intimate, meaningful relationships were with other men. Sometimes the relationships were sexual, but even if two particular men were not in a sexual relationship they cherished their friendship deeply. Forster probably knew he was homosexual before coming up, but there can be no doubt that the relationships he formed here helped him accept that about himself, with one result being his novel of homosexual love, Maurice. He shared the manuscript only with friends during his lifetime, such as in this 1915 letter to Dent in which Forster asked Dent to read the manuscript but ‘please only speak of its existence to [Greenwood], Dickinson, or Sheppard, as it has to be as dead as a secret can be.’ For more on Maurice see another of the Archive Centre's regular series of on-line exhibitions.

Goldsworthy 'Goldie' Lowes Dickinson (1862-1932, KC 1881) lived in the rooms above the arch in Gibbs to which Forster was a frequent visitor during Dickinson's life. Forster and edited Goldie's autobiography. John Tresidder Sheppard (1881-1968, KC 1900) became an Apostle soon after Forster graduated. Sheppard eventually became Provost.

![Forster's great-aunt Marianne Thornton in 1830 [EMF/27/947] Forster's great-aunt Marianne Thornton in 1830 [EMF/27/947]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/emf-27-0947_crop.jpg)

His father died while Forster was an infant and he was raised by his mother and other female members of the family in a variety of residences. Until he and his mother inherited from his paternal great-aunt Marianne Thornton, at right, their living arrangements were precarious, and even when they were financially secure, they moved house frequently. As an adult Forster retained bolt-holes in London but generally lived with his mother for most of his life.

They lived at Rooksnest for ten years from 1883-93 (the photo shows him seated on a pony held by his mother). This house was the inspiration for the eponymous Howard's End.

![West Hackhurst 1906 [EMF/27/195] West Hackhurst 1906 [EMF/27/195]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/emf-27-0195.jpg)

Forster’s aunt Laura commissioned her brother, Forster’s architect father, to build West Hackhurst on land she leased. Forster visited the house as a child and in 1924 he inherited the house and the leasehold on the land. In December of 1945 (the year his mother died) when Forster returned from India he was told – two days before his 65th birthday – that he must vacate the house as the owners required the land for their own use. King's offered him an Honorary Fellowship and rooms in College.

First pick from Forster's extensive and valuable personal library was one of the great gifts the College received at his death. The collection incorporated books he'd inherited from his Aunt Laura, including a set of The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin (1887), given to Laura by the editor, Darwin’s son Francis. Laura was a lifelong friend of Darwin’s daughter Henrietta. The leatherwork cover of Forster's copy (shown below) was made by Laura. In 1879 Charles Darwin himself stayed at West Hackhurst; see his letter to Laura below. (This connection was the subject of a King's special collections blog.)

The room rent diagram (right) reflects how during the 1920s and '30s, his beloved tutor Wedd lived in the rooms later occupied by Forster.

Comparison of the mid-20th century photographs of his King's rooms with the late-19th century drawing room at West Hackhurst shows how lovingly Forster remembered that old house. Even the portraits are unchanged. The photos of Forster's rooms on A staircase (now part of the Grad Suite) were taken between 1949 and his death in 1970. Photographers: Edward Leigh (to 1968) and Lettice Ramsey (1970)

Forster died in 1970 at the age of 91. He left most of his personal effects to individuals, in order that his rooms NOT become a place of pilgrimage, as described in the letter (below) from Provost Leach to the K.C.S.U. President M.G. Segal (KC 1969). He mentions the 'longstanding informal understanding that the B.A.s would have a priority claim on at least parts of Morgan Forster's set when it became available', and so it came to pass.

Rather poignantly, one of the objects for which Forster did not specify a recipient in his will was a fireplace surround that his father had designed and which he and his mother had moved to every home they shared – shown in the photographs below at Rooksnest in 1885, in Forster’s College rooms in 1949, and in a 21st century photograph of those rooms.

![Menu for Forster's 80th birthday dinner in the Hall [KCAR/5/4/1/11] Menu for Forster's 80th birthday dinner in the Hall [KCAR/5/4/1/11]](https://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/page-images/kcar-5-4-1-11-19590109-menu_crop.jpg)

The Senior Common Room suggestion books reflect some of Forster's character, and his interactions with fellow Fellows. His first appearance is a signature in support of a proposal to stop taking 'The Field' (a magazine for squires), and as he gained confidence in his new home he contributed to a suggestion 'That the Combination Room Notice Board should not be used for controversial political propaganda.' Forster's suggestion, 'That the suggestion at the top of this page should be adopted, and that a Notice Board should be placed in the Octagon, where notices of the type referred to could be freely displayed' is a thoughtful compromise that respectfully acknowledges everyone's right to be heard.

Although he rarely sat on committees, Forster did participate in major Governing Body decisions as seen below - in 1966 heading to Chapel for the vote for a new Provost, and sitting on Congregation. In 1960 the College decided to demolish the dilapidated seventeenth-century Central Hotel on St. Edward’s Passage and build Market Hostel. This was preceded by a public outcry and heated debate. Provost Annan kept a file on the subject which includes part of a letter from Forster arguing for preservation of the Central Hotel. Forster valued it 'not for aesthetic or anecdotal reasons but because it is an essential part of a small but exquisite complex. If we demolish it the complex vanishes. No modern building however tactful can replace it. We shall provide another example of the tidying up and dulling down that afflict Cambridge and other old places.' Forster was unable to attend the relevant Congregation vote, and the College reported that the decision to demolish was unanimous. The photograph below must have been taken shortly before the demolition. Forster has annotated it 'St Edwards’ Passage, before destruction of Central Hotel. Now Lavatory Lane'.

Forster's 80th birthday lunch was such a grand affair that the Times covered it. The occasion was taken by the Greek Ambassador (George Seferis) to make a presentation. In memory of Forster's championing of the poetry of CP Cavafy, one of whose poems was entitled 'Demetrius Sôtêr', Forster was presented with a silver tetradrachm of Demetrius I Sôtêr (162-150 BC).

| Year | Novel title |

|---|---|

| 1905 | Where Angels Fear to Tread |

| 1907 | The Longest Journey |

| 1908 | A Room with a View |

| 1910 | Howards End |

| 1924 | A Passage to India |

| 1970 | Maurice |

The Longest Journey (first page shown below in manuscript draft) is to some extent about Forster's time as a student at King’s, and opens with a meeting of the Apostles discussing whether a cow on scholar's piece exists, if it is dark and they cannot see her. He captures the undergraduate excitement of discussing Philosophy!

Passage to India. Forster first visited India in 1912-13 in the company of fellow Apostles Robert Trevelyan (Trinity College, 1891), Goldie Dickinson and Malcolm Darling (KC 1899, a rising star in the Indian Civil Service). In 1921 Darling arranged for Forster to return to India for nine months as the Private Secretary to His Highness the Maharajah of Dewas State Senior.

Forster has repaid the College richly for whatever part it played in his novels. His copyright is now owned by King's and even though his published works are out of copyright in the United States, they are still in copyright in the UK and many other countries. Licensing them continues to benefit King's, be it a Merchant-Ivory film or foreign language editions of his novels.

Forster could play the piano and he had an ear for, and passionate interest in, music. His diary while an undergraduate includes several mentions of concerts he attended including some in Chapel. For example on 11 May 1898 he went to hear a concert including a Beethoven quartet, and 19 May 1898: 'Went to 5.0 chapel. Handel’s ‘Lift up ye Gates’; beautifully sung though the choir is scarcely Handelian in sentiment. At 5.0. this morning Mr Gladstone died. We had Beethoven’s funeral march in chapel.' An entry for 20 April 1898 records a visit to Queen's Hall for a concert including Beethoven, much like the one at the beginning of Chapter 5 of Howard's End: 'It will be generally admitted that Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is the most sublime noise that has ever penetrated into the ear of man ... the passion of your life becomes more vivid, and you are bound to admit that such a noise is cheap at two shillings. It is cheap, even if you hear it in the Queen’s Hall, dreariest music-room in London ...' That passage is not present in the King's manuscript but the subsequent conversation in the novel, criticising Queen's Hall, certainly is. An entry in his 1908 diary reflects a similar concert: 'on Sunday going to the 5th Beethoven at Q’s Hall. S.& I argued about classical education and Rudyard Kipling.'

Forster feigned ignorance in writing to Dent about a 1902 German production of The Magic Flute he had attended in Nürnberg: 'I enjoyed the opera very much ... I am as yet too inexperienced a goer to listen properly to the music + singing ... As it was, I understood little except the tragic death of the boa constrictor in the first few bars.'

The College kept, from Forster's 'library', three sets of records: Beethoven's Romances for Violin and Orchestra Nos. 1-2, Schubert's song cycle 'Winterreise", and Beethoven's Fifth.

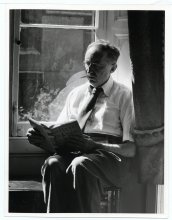

At King's, Forster would have been steeped in the tradition of iconoclastic, critical thinking. Forster's published essay collection 'Two Cheers for Democracy' includes criticism of the populist rise of Nazism and nationalism, defences of the value of the individual, and the value of art in the face of totalitarianism. His 'bachelor don' attitude is apparent in the preface where Forster explained that the title was suggested by one of his 'younger friends ... as a joke' - at King's in particular there is a relative equality, a mutual respect between Fellows and students.

The book included an essay entitled ‘What I Believe’, first published as a separate edition in 1939 by Forster's friends Virginia and (fellow Apostle) Leonard Woolf at their Hogarth Press. The essay is full of what Forster's biographer Nicola Beauman attributed to Apostle G.E. Moore's 'vision that embraced truth, beauty and personal relations and that eschewed the mechanical and the socially divisive.'

In 1955 (aged 71) Forster wrote a letter to the editor of The Twentieth Century which was planning an issue devoted to Humanism. Forster wrote of his belief 'in the individual, and in his duty to create and to understand and to contact other individuals. A duty that may be and ought to be a delight…Wherever our race came from, wherever it is going to, whatever his own fissures and weaknesses, [the individual] himself is here, is now, he must understand, create, contact.'

Forster was sceptical about 'progress' if it diminished humanity. He witnessed the landing of the first cross-channel flight on July 25, 1909, and sixty years later the first man on the moon. The artist-in-residence at the time watched the moon landing with other Kingsmen on the communal television in the Octagon, and recalls that Forster commented ‘I’m not sure they should be doing that’.

Echoes of the Humanist Goldie Dickinson and Classicist Oscar Browning can be heard in Forster's diary entry in 1908: 'Last Monday a man – named Farman – flew a ¾ mile circuit in 1 ½ minutes. It’s coming quickly, and if I live to be old I shall see the sky as pestilential as the roads. It really is a new civilisation. I have been born at the end of the age of peace and can’t expect to feel anything but despair. Science, instead of freeing man – the Greeks nearly freed him by right feeling – is enslaving him to machines.' Thinking of airport delays, or frustrating attempts to resolve a computer problem, the descriptors 'despair' and 'enslavement' are rather apt.