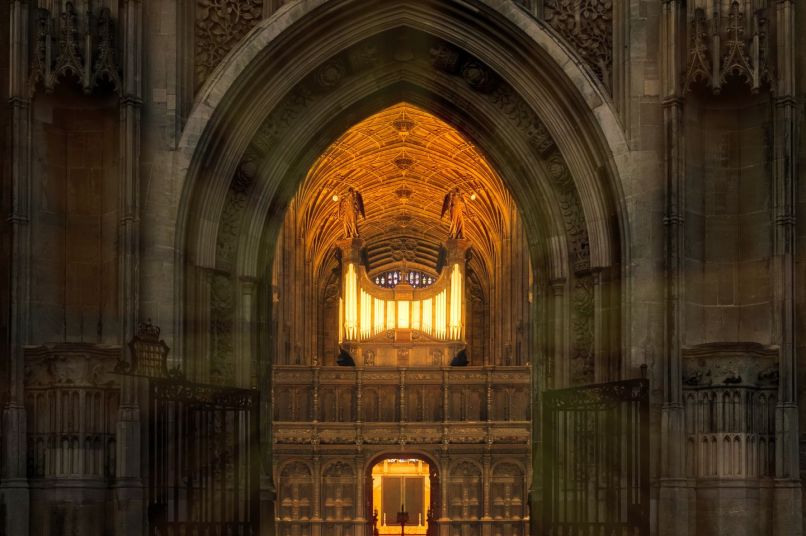

The Chapel Organ

The organ in King's College Chapel is a striking feature whose sound is inextricably associated with that of the Choir

About the organ

The Harrison & Harrison organ in King's College Chapel is, like the College Choir, famous the world over. The case and gilded pipework, which surmounts the 16th century screen, is a striking feature of nearly every depiction of the interior of the Chapel, while the instantly recognisable sounds of the instrument have become inextricably associated with those of the Choir.

The organ fulfils an important role in the religious and musical life of the College while also serving as an educational resource. Many of today's leading musicians have held the position of Organ Scholar at King's.

Organ history

The early organs

It is thought that there were two organs in King's College Chapel as early as the 1530s. Records show that two small organs were moved from a temporary Chapel used during the construction of today's Chapel.

At least one of these organs was then removed in 1570 at the orders of the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth and the pipes were sold by Roger Goad (Provost, 1570-1610).

On 22 June 1605, the renowned organ builder Thomas Dallam began work on a new organ in the Chapel. The accounts for his work have survived, showing in detail the materials and hospitality provided by the College while the work was done.

The order for this new organ, totalling £370, was considered so important that Dallam closed his London factory and took his men to Cambridge, where they worked for fourteen months. It is believed that around 25 years later this organ was moved from the East End of the Chapel and mounted on top of the screen.

Although the Long Parliament ordered the removal of the pipes half a century later the wooden case was left intact, mounted on what is one of the finest Renaissance screens in the country.

Successive re-buildings were undertaken by Lancelot Pease (1661), Thomas Thamar (1673-7), Renatus Harris (1686-8), John Avery (1802-4), and the firm of William Hill (1834, 1859, 1889 and 1911).

The organ in the 20th century

In 1934 the organ was enlarged and rebuilt in its present form by Harrison & Harrison, with some of the Hill pipework retained and re-voiced. The specification, drawn up in consultation with Boris Ord (Organist 1929-57), included separate mutations on the Choir Organ, unusual in England at that time.

Minor changes were made in 1950, when the Pedal Fifteenth and Mixture were added. In 1968 the organ was overhauled and several new stops were provided (11, 12, 22, 48 and 50), four old ranks being displaced. Further restoration work was carried out in 1992, when the console was renovated and the electrical system modernised. Further essential repairs took place in 2003 and 2009, during which it became clear that a major restoration would be needed.

Timeline of work on the organ:

1934

Rebuilt and enlarged by Harrison & Harrison.

1950

Minor changes (Pedal Fifteenth and Mixture added).

1968

Significant overhaul, including re-leathering, the replacement of the Great power motors, and the addition of six new stops.

1992

Essential repairs and modernisation (console and electrical system).

The organ case

There is some uncertainty about the history of the wooden case, which is one of the oldest in England. While it has traditionally been thought that the main case survives from the original Dallam organ of 1605-6, it is more likely that only some decorative components may originate from that time. Its current form is more likely to be a contemporary of the Choir case, which dates from 1661.

The front pipes were originally coloured and patterned; the plain gilding dates from the eighteenth century. In 1859 the main case was increased in depth to accommodate the enlarged organ, the console being moved from between the main and Choir cases to its present position on the north side.

Today, the Great and Swell Organs and the Tuba occupy the main case, facing east; the Choir Organ is at the lower level behind the Choir case; the Solo Organ and most of the Pedal stops are placed within the screen on the south side.

Major work in the 21st century

Different levels of work have been carried out in the first decades of the 21st century, including replacement of the pedal board, leak repairs and pipework maintenance.

In 2003 three front pipes in the northwest tower of the organ case were repaired and reguilded. These pipes, which are thought to be at least 300 years old, were collapsing under their own weight. They are no longer speaking pipes, so their deformation had not affected the sound of the organ; but it was obvious to the eye, and in time would have presented a hazard.

In 2009, three front pipes in the southwest tower, collapsing under their own weight, were repaired and reguilded in the same way as work to other front pipes in 2003.

A ‘stepper’ system was added to the console. This electronic system provides conveniently located stepper pistons that advance through the various combinations of stops that have been selected on the general pistons.

The memory system of the console was upgraded so that the eight general pistons now have 512 levels of memory and the divisional pistons have 16 levels.

The keyboards and pedal toe sweeps were removed to make changes to the piston layout. At the same time the four keyboards were overhauled.

In 2016 the organ underwent the most significant restoration since the 1960s.

Today’s instrument remains fundamentally as it was designed to be at the time of its restoration in the mid-1930s, but after many years of frequent use it became unreliable. Major work was undertaken to ensure that it continues to function optimally for the next generation.

Thanks to several significant donations which funded the work proceeded over 9 months, with Chapel services continuing during much of that time. The pipework was removed from the case and, with the exception of the largest basses, returned to the Harrison & Harrison workshop in Durham for cleaning and repair. Works to the empty organ case, including cleaning, surveying and restoration, took place while the pipes were away.

The inner workings of the organ were repaired and reorganised which benefitted from new technology and materials. There was no significant tonal alteration, except that, with cleaning, the sound has returned to a former brightness.

How the organ works

The organ in its current location on top of the screen dates back to a two-manual organ built by Thomas Dallam in 1605. It is thought, however, that only a few decorative components date from this time, and that the case is more likely to originate from the 1660s. Over the centuries the organ has undergone numerous restorations and re-buildings.

All the (musical) sounds made by the organ are made by the flow of air through pipes. Electric current is used in control systems, such as in the console and the wind system. The actions are electro-pneumatic.

The console consists of four manuals (keyboards), a pedalboard, stops and pistons. The four 61-note manuals control four different divisions of the organ: Choir, Great, Swell and Solo. There is also a 32-note pedal-board.

The pipes

Some of the smallest pipes can be measured in millimetres, while the largest 32’ basses which run horizontally inside the screen are big enough for a fully-grown person to climb inside.

Thanks to the hard work of the organists at King’s and the tuners of Harrison & Harrison, the organ is rarely heard having problems. Occasionally though, as with mechanical pipe organs, things do go wrong. One example is called a ‘cipher’, which is when a note continues to sound despite the organist releasing the key. For major events, such as A Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols, experts from the organ builders Harrison & Harrison are on-call in the Chapel. The 2016 restoration greatly improved the reliability of the organ.

Playing the organ

There are three organists at King’s: The Organist and Director of Music and two Organ Scholars. Day-to-day playing at choral services and at concerts is generally undertaken by the two Organ Scholars, who are undergraduate students at the College. Recitals take place regularly during term time, which are often played by visiting organists.

The player sits at the console in the upper north side of the screen. The console consists of four manuals (keyboards), a pedalboard, stops and pistons. There are audio and video systems as well.

How does the organist keep time with the choir?

The organist has a number of video cameras at their disposal so that it’s possible to follow the conductor or to take cues from other aspects of a Chapel service. However, since the organist sits quite a distance from the choir stalls, it can be quite a challenge to accompany a choir: the organist is required to play ahead of what he or she can hear from the choir in order for the organ and choir to sound together; something that can take years of practice.

The challenges of playing the Chapel organ as part of an ensemble are largely as they were a hundred years ago. With advances in technology though, a small number of technical aids have been added to make the rehearsal process in particular a little easier. A remote-control video system allows the organist to view both the main Chapel and the Ante-chapel. A wireless microphone worn by the conductor allows the organist to listen during rehearsals, and a ‘talkback’ system allows the organist to talk back to the conductor. The organist also has an at-console audio recording and playback facility linked into the Chapel’s recording system, used for reviewing a play-through during rehearsals. While it is possible for the organist to use a live-monitoring facility through headphones to overcome time delays between ensembles and the organ, King’s Organ Scholars do not use this facility for Chapel services.