Queen Elizabeth visited Cambridge in August, 1564 for several days. It was decided she would stay at the King’s College Provost’s Lodge (that is, the master’s lodge). Four plays were prepared by University members as part of the entertainment. The plays were initially planned for performance in the College Hall, but it was deemed too small and a specially built stage in the King’s College ante-chapel was used instead.

King’s College has other ties to the throne. In the pages below you will find details of the College at the time of the royal visit and the preparations made for it, the College’s relationship with Elizabeth I as major landlords, and other ties she had with the College.

The England ruled over by Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603, Queen from 1558) was a triumphant military power and culturally very rich. The burr under her crown was that Catholics considered her to be illegitimate and so ineligible for this enviable throne. Travels through England with her Court, appearing before her subjects with charm and in majesty, allowed her to consolidate power, establish the support of her subjects, and assert her right to rule. It was one of those travels that brought her to Cambridge in August, 1564.

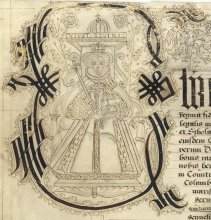

Elizabeth dei gracia Anglie Francie et Hibernie Regina fidei defensor etc, OMNIBUS ad quos presentes littere peruenerint Salutem.

Elizabeth, by the grace of God Queen of England, France and Ireland, and defender of the realm, TO ALL WHO SEE THIS, Greetings.

So begins a grant of Sampford Courtenay manor from the Queen to King’s College, shown above.

Note the symbols for royal power in England (lion, rose and crown), Wales (dragon), France (fleur de lys) and Ireland (harp) at the top of the charter. The first line is formulaic and can be found on any ancient royal charter, though the specifics change from time to time. The lovely decorated lettering is more ornate than strictly necessary, indicating a document of great importance.

Other evidence that this is an important document are the use of Latin and of the Great Seal.

The Great Seal on this charter is larger than that of previous monarchs, 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter. It follows the usual pattern for Great Seals, depicting the ruler enthroned on one side and on horseback on the other. The horseback side usually depicts a king in battle dress, but for this Queen, who could be head of the armed forces in name only, both sides show her with the orb and sceptre. She would not let England forget that she was Queen.

For less important documents she could use the privy seal, which is comparable in size to the Great Seals of her predecessors. The privy seal has her enthroned with orb and sceptre on one side, and the royal crest on the other. It is almost 4 inches (9.7 cm) in diameter. In this case the seal is attached to a 1591 exemplification (certified copy) of the fine (right to collect certain fees) for Sampford Courtenay.

Charters like the one on the previous page were part of the royal display of wealth and power, and the Fellows of King’s College were in no doubt as to the quality of entertainment and hospitality they would be expected to provide during a royal visit. Fortunately they were already well on the way, because of a planned (but not executed) royal visit in 1536. Expansion and renovation of the Provost’s Lodge continued from 1536 right up until Elizabeth’s 1564 visit.

Early renovations mentioned in the accounts (see below) included demolitions, removal of a wall to create one large room and a gallery in the newer part of the house, and further repairs carried out in the rest of the house ‘against the king’s arrival’. In 1546 the porch and its upper room - manor-houses of the time frequently had rooms above the porch - were glazed with Normandy and Burgundy glass, which were the highest quality glass available at that time.

The high standard of furnishings might have contributed to Elizabeth’s decision to reside at King’s when she made that visit to Cambridge; the fact that the Provost of King’s made nearly as much as the heads of the 14 other Colleges (excluding Trinity) put together, might also have contributed to that decision. In any case the Queen enjoyed her stay and declared that she would have stayed longer if the beer had not run out.

By tradition until 1689, the Crown had nominated the Provost, or head of the College. The nominee would then be voted in by dutiful Fellows even though the statutes granted them the sole right to elect the Provost. When Elizabeth visited in 1564 her host as Provost was Philip Baker, whom she had nominated six years earlier - a privilege she enjoyed in the first year of her reign.

Ours being a royal foundation, we occasionally bump up against the sovereign. We were endowed by Henry VI with land to support the College, which meant we were Lords of the Manor on desirable estates. Many years after her Cambridge visit there arose a dispute with Elizabeth I about whether she ought to have the right to name the landholder of a College property (in Sampford Courtenay, Devon). One of her negotiators in that case was Francis Walsingham, better known as her spymaster, who was perhaps assigned to this duty because he had been a Pensioner (a student paying his own way) at King’s, from 1548.

Compared to the charter on the 'Elizabeth, By The Grace of God Queen Of England' page (link below), the letter shown below is apparently of less significance. The Queen asked her ministers to write it, it is not decorated, it is in English rather than Latin, and it does not bear a royal seal. It was signed by the Lord Treasurer William Cecil, first Baron Burghley (1520/21-1598), and the Principal Secretary Francis Walsingham (c.1532-1590).

Another Kingsman in the Queen’s household was Walter Haddon. Haddon came up to King’s in 1533 and was a member of the College until 1552. As the best Latin writer of his day he was chosen to translate the Book of Common Prayer into Latin in 1560. Elizabeth officially authorised its use at Cambridge and Oxford Universities, and Eton and Winchester. Haddon accompanied Elizabeth I to Cambridge on her 1564 visit. The following year the queen granted him the site of the abbey of Wymondham, Norfolk, with its manor and lands.

Walter’s son Clere Haddon, an exceedingly promising King’s student, drowned in the Cam in 1571. Probably because of this terrible loss, Provost Goad made a decree, recorded in the College’s archives (shown below), forbidding all members of the College, including servants and Choristers, to swim or bathe in rivers or streams anywhere within Cambridgeshire.

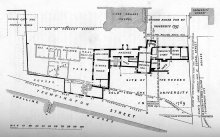

The College was a very different place when the Queen visited in 1564. Since the early 19th century the College buildings have all been south and southwest of the Chapel but when the Queen visited, all the College buildings were located to the east and north of the Chapel. The Provost’s Lodge was on what is now called King’s Parade, and the rest of the buildings were in Old Court, now the Old Schools site.

Originally the plays were to be performed in the College Hall in Old Court. In 1564, royal progress from the Provost’s Lodge to the Hall would have been roundabout, probably either through the Chapel and out the north door or around the south and west sides of the Chapel, shown below on Loggan’s 1688 plan of the College site where ‘F’ marks the Old Court and ‘1’ is the Chapel. The approach from the Provost’s Lodge to the Provost’s entrance at the northeast corner of Chapel, however, was much more convenient and the Chapel was chosen over the Hall, to host the theatrical productions.

The images below show that the entrance to the Old Court was grand enough to suit the queen but the drawings of the gabled Hall show that it may indeed have been unsuitable for a royal entertainment. The Hall had been extensively repaired two years previously, possibly even enlarged to its 1635 size of 25 feet x 40 feet (7.6 x 15.2 m), but it was still less grand than the ante-chapel which is 40 feet wide and 120 feet long.

Besides 70 Fellows and Scholars, 16 choristers, 10 chaplains and 6 lay clerks, the College’s founder Henry VI specified in the College statutes (which were in force until 1862) that all servants, that is, staff members, must be male, except possibly the laundress if a man is not available. The statutes list those staff that are to be supported by the College: several porters, a victualler, a butler, two bakers, a head cook and three assistants, a valet and two assistants, a launderer, and a gardener. The servants at the time of Elizabeth’s visit are named in the list below.

Amongst the fellowship during Elizabeth’s visit (listed in the image below) were:

The Provost, Doctor Baker

The University Orator during Elizabeth’s visit, William Master. At the 1564 royal visit he welcomed the Queen with a half-hour speech in Latin. She commended his memory.

Thomas Browne, Dean of Theology, who incurred expenses in preparation for the visit (see the page 'Fit for a Queen', link below).

Thomas Preston, who impressed the Queen with his acting so much that she gave him a £20 annuity. He also wrote the play Cambises which Falstaff ridicules (in Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part I) when he says 'I must speak in passion and I will do it in King Cambyses' vein'. Preston was Dean of Arts in 1564, and a lecturer.

William Wickham who was just finishing his MA in 1564. He later became a chaplain to Queen Elizabeth, then Bishop of Lincoln (and thus the College’s Visitor) and finally Bishop of Winchester. He preached at the funeral of Mary Queen of Scots.

On the evening of Sunday, 6 August 1564, Queen Elizabeth I entered King’s College Chapel for the first of four plays. She walked down the choir, through the screen doorway, and across a temporary wooden bridge to the stage in the ante-chapel, where she sat on the south side of the stage.

The second play she saw, Dido, was produced and acted entirely by Kingsmen and it was spectacular, including the construction of the walls of Carthage and probably producing the sound of artificial thunder.

For costumes, they had old religious vestments. By the end of the reign of Henry VIII the Catholic Church was out of favour in England and Papist religious items were frowned upon. Vestments were prohibited under Edward VI and so were turned to other uses such as costumes for theatre. With Mary’s accession they could be turned back into vestments, but the process had by no means been completed by the time of Elizabeth’s accession.

The list below, made in 1554 (ten years before Elizabeth I’s visit) describes vestments that had been turned into costumes. The costumes marked with a cross mark (see above) were transformed back to vestments but the others were probably used in at least two of the performances she saw.

Provisions were sent to King’s in advance of the royal visit but the College still incurred substantial expenses in entertaining the Queen and Court. Fourteen pounds of candles were laid in, dozens of day-labourers were hired at 8 pence (8d) per day, chimneys and plasterwork were repaired, keys made, cellars cleaned and the churchyard mowed, all in advance of the royal visit.

The Queen, upon her arrival in Cambridge, walked along the lane from Queens’ to King's College which was strewn with rushes, hung with flags, boughs and coverlets, and lined with University students and fellows. Rushes were also used as flooring at the west end of the ante-chapel which was not paved at the time.

The pages reproduced below are from the College accounts for the summer of 1564, from the special section devoted to necessary expenses made for the visit of the Queen.

Payments to local tradesmen include 3s 5d paid to Oliver Green for nails for the stage – that’s just over 5 days of wages for a labourer! This would have been the stage originally built in the Hall - the Queen paid for the stage built in the Chapel. Christopher Wallis was paid 25s 10d for the casement on top of the screen (the rood loft) where the ladies stood. (The organ which is there now is a later installation.) Male courtiers watched the play from beneath the screen.

A King’s Fellow Tom Brown was reimbursed for his expenses in connection with the actors (6l 16s 4d), and 4s was paid for the drummers and flutes.

Further details of the pomp and preparations necessary for the Queen’s stay can be inferred from the expenses of 3l 6s 9d paid to the Queen’s footmen for use of their canopy which was carried over the Queen (though in this case it was carried by four Cambridge men with Doctorates), 8s 7d paid to a carpenter David Truman for joinery work in the Lodge including removing beds and wardrobes and putting them back after the Queen had left, and 5s for a velvet-bound communion book, a gift for the Queen.

Each College prepared verses celebrating the Queen, and they were bound and presented to her - that volume is now held in the University Library (MS Add.8915). One of the final expenses at King’s College for this visit was 12d for binding its own book of verses in crimson velvet.

-

Austen Leigh, Augustus: Cambridge University College Histories: King’s (London: FE Robinson & Co., 1899), pp 241-255.

-

Clark, John Willis: 'On the Old Provost's Lodge of King's College, with Special Reference to the Furniture'. In Communications of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society vol. IV (Cambridge: University Press, 1881), pp 285-311.

-

Morris, Christopher: King's College: A Short History (Cambridge: University Press, 1989).

-

Nichols, John: Progresses, Public Processions, &c. of Queen Elizabeth I..., vol. I (London: John Nichols and Son, 1823), pp 151-188.

-

Rokison, Abigail: ‘Drama in King's College Chapel’. In King's College Chapel 1515-2015. Art, Music and Religion in Cambridge, ed. Jean Michel Massing and Nicolette Zeeman (London: Harvey Miller, 2014), pp 221-237.

-

Storer, James Sargant: Illustrations of the University of Cambridge (Cambridge: W Styles, 1820?).

-

Willis, Robert and John Willis Clark: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge... vol. I (Cambridge: University Press, 1866).