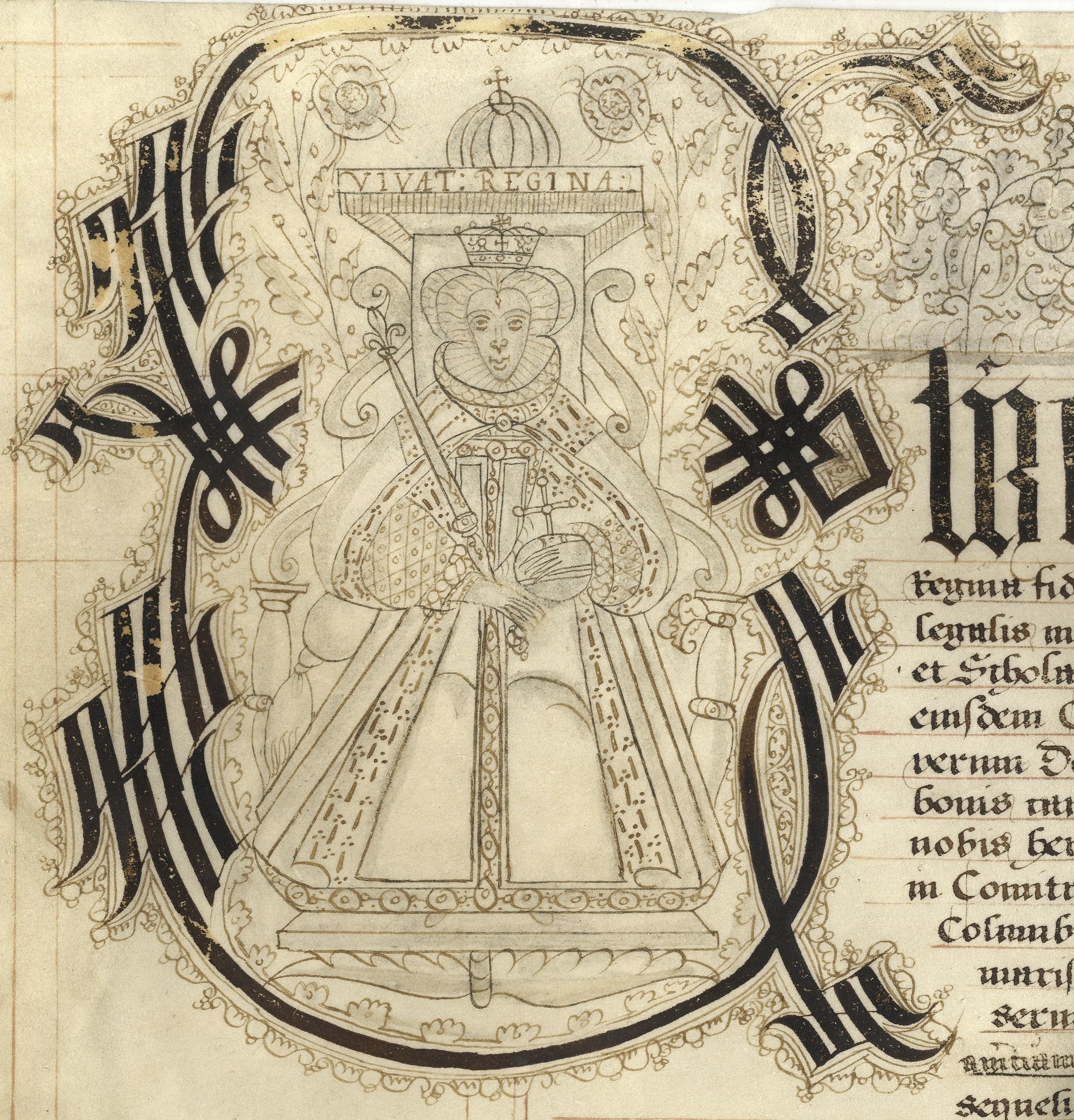

Of course, women have been a part of King’s since its inception. Isabella, the sister of our first Provost Robert Wodelarke, was married to John Canterbury who was Clerk of Works for building the Chapel. How much she had to do with her husband being given that job by her brother, we’ll never know. And the College probably always had laundresses and bedders, though their names have not been found amongst the older College papers.

The surviving records that comprehensively list women ‘servants’ only go back to about 1900.

At King’s as elsewhere in England during the First and Second World Wars, professional opportunities for women were greatly increased.

Letters from Dadie Rylands’ 1941-45 bursarship provide evidence of such things as how women were paid at that time.

King's was almost the first college to admit ladies to the floor of its Hall – even the servers were all male. In 1947, despite rationing, the College held the prototype Summer Supper party. All the guests were to be women. In 1958 Fellows and students were first allowed to bring lady guests into Hall on certain occasions or nights of the week. On Founder’s Feast however, it took a few years before the women were allowed down from the gallery.

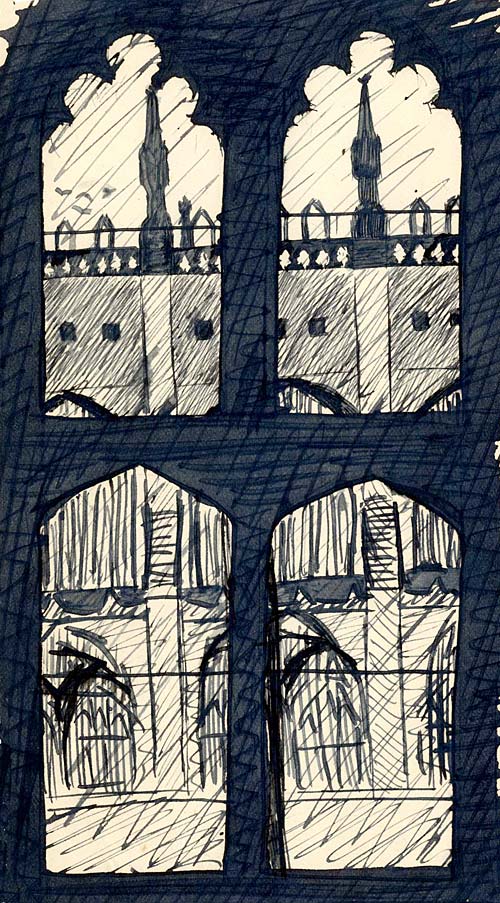

Dadie Rylands’ sitting room (now the Accounts Office) was famously described in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Shortly before Virginia Woolf wrote of a dinner there, it had been painted by artist Dora Carrington and her decorations survive.

By 1897 all British higher education facilities were admitting women to full membership, except Oxford and Cambridge. King’s has always supported women’s education in the University:

| 1869, 1871 | Girton and Newnham were founded. Kingsman Oscar Browning persuaded King’s to allow female members to attend college lectures, a sensation in its time. |

| 1882 | The first women took Tripos exams. They didn’t get degrees or University membership, they got a certificate. |

| 1897 | The University voted against a Grace allowing women to be granted degrees. 661 voted for it, 1707 voted against it. |

| 1921 | Women were allowed to earn titular degrees but not University membership. |

| 1948 | Women were allowed full University membership. |

| 1954 | New Hall was inaugurated. King’s made the largest financial contribution of the colleges. |

| 1972 | King’s, Churchill and Clare were the first Cambridge all-male colleges to admit women undergraduates. |

Anne Clough (1820-1892) was the first Principal of Newnham. The fact that her funeral service began in the King’s College Chapel was a clear statement of the College’s support of women at the University.

Sir George Prothero (King’s Fellow from 1872) wrote in 1878 to the Provost that he had no objection to women attending his lecture: ‘I should be glad myself if they were admitted, since it seems a pity, if it can be done without impropriety or additional exposure, that they should not have the same advantages in University Education as the men’ [KCM/38/8] although he recognized that King’s was not acting in a vacuum – they might not want to set a precedent that put other colleges in awkward positions.

An 1880 letter from Alice Lushington (Hughes Hall) to Oscar Browning [OB/1/995A] shows some of the complications of the unofficial exam system. The women were examined in separate rooms from the men and she had to provide ink, blotting paper and other supplies as well as invigilators.

Kingsmen were not uniformly pro-women’s academic rights. Virginia Woolf’s cousin JK Stephen founded the Walpole debating society at King’s in 1891, and the first motion was ‘That the Female Sex Stands in Need of Repression’. Sadly, the motion was carried. But three years later the Walpole Society passed ‘That this House Welcomes the Advent of the New Woman’, and in minutes from 1896 [KCAS/20/1/3], they voted in favour of the admission of women to University degrees.

In a letter Ellen McArthur (secretary of the Cambridge Women’s Training College, later Hughes Hall) wrote to Kingsman Oscar Browning [OB/1/1008A], in 1906, she expressed the fact that equal opportunities for women at the University necessitated better primary teaching in the girls’ schools – early educational foundations for women had to be in parity with those for men.

Kingsman John Edwin Nixon tried to get as many King’s alumni as he could to come to Cambridge for the 1897 vote about women’s degrees, which was one of the biggest in the history of the University up to that time. He even arranged that special trains from London be laid on.

Mrs. Sidgwick (founder of Newnham College) wrote a letter complimenting Nixon on his flysheet [Misc. 32/7].

In 1895 Elizabeth Hughes (founder of Hughes Hall), Oscar Browning and Mr. Iliffe had a misunderstanding. She wrote to Iliffe that ‘there are some things that I could appropriately say to you if I were a man, that I must not say because I am a woman.’ [OB/1/829] Politics in Cambridge is difficult enough without having to fight propriety as well.

The messengers pouring out of Senate House in the 1897 photograph below were carrying news of the negative result. Undergrads had no vote but obviously had an opinion, and the banners indicate they weren’t all pro-women’s-degrees.

When Richard Bevan Braithwaite (1900-1990, KC 1919, Fellow from 1924, Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy 1953–1967) was baptised in the College Chapel, EM Forster noted in his diary (May 26 1948) ‘women to wear academic gowns because he helped them to get degrees.’

Oscar Browning (1837-1923) came up to King’s in 1856 and then went off to be a housemaster at Eton. His affections tended towards boys and young men but he did support higher education for women. He wrote a biography of Marian Evans (George Eliot), and his work as an educationalist upon his 1875 return to King’s put him in regular collaboration with the pioneering women of the University.

Miss Welsh, mistress of Girton, circulated a notice of thanks shortly after the 1897 vote. It is not clear which committee she refers to – in 1896 the University established a Degrees for Women Syndicate but the only Kingsman of those nine syndics was Arthur Berry (KC 1892). In any case Miss Welsh’s letter, sent to Oscar Browning, reflects the University women’s gratitude to him.

The women in the University wouldn’t take no for an answer. In 1920 another University proposal was made to admit women as members, again it was rejected. In 1921 the University did approve a grace allowing women to have titular degrees, though not full membership. Although King’s had had a majority in favour of the 1920 proposal, in 1925-6 the commissioners appointed under the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge Act required King’s to change its statutes to bring the College into line with University statute G(IV)2 specifically excluding women. The stipulation ‘No woman shall be a member of the college whether on the Foundation or otherwise’ was incorporated into the statutes of King’s College as G(3).

In a 1921 letter to the editor of the Cambridge Review written by JM Keynes (second bursar of King’s at the time) he describes such ridiculous prevailing situations as that Tripos-required courses taught by women couldn’t be advertised in the regular course list. He also points out that the proposed scheme was supported by a substantial majority of Professors, Readers and University Lecturers.

The official record sometimes ignores what happens behind the scenes. In a 1921 letter from Keynes to Will Spens (Corpus Christi College), Keynes reports a very interesting conversation with [Herbert Henry] Asquith, head of the 1920s Commission and Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916, with whom he ‘happened to be staying’.

In 1948 the University finally allowed Girton and Newnham to be full member colleges and their students full members of the University. Richard Braithwaite and Kenneth Harrison of King’s College played a key role in this development. It took another 18 years before King’s had an opportunity to remove its statute G(3).

Once women became members of the University the way was paved for King’s College to admit women, but changes in statute require Privy Council approval. By the 1960s the social climate supported erstwhile all-male colleges admitting women, and King’s took advantage of a major revision of its statutes (submitted for royal approval in 1966) by voting to demote the female-exclusion clause to an ordinance so that it required only College Governing Body approval - the College could decide in its own time how and when to admit women.

In November, 1968 the Governing Body considered a paper prepared by the JCR recommending co-education at King’s. The GB decided to...set up a subcommittee!

In further support of women at the University, during the 1960s King’s gave money to Girton (£2000, though the Provost had only asked for £1000), Newnham (£2500) and Lucy Cavendish (£1000). That’s equivalent in today’s money to over £20,000, £25,000 and £10,000 respectively. The Governing Body was also addressing the issues of women at High Table and in the SCR.

In May 1969 the subcommittee reported to the Fellows.

After some objections, recorded in a letter from George Salt and responded to by Provost Leach, the Fellowship (surprisingly) did not take up Leach’s option to ‘adopt a policy of delay and see what happens in Clare and Churchill’, instead they voted almost overwhelmingly to accept women at King’s in principle.

King’s, Clare and Churchill Colleges collaboratively investigated the possibilities and implications of co-education, and were the first of the Cambridge all-male colleges to admit women. The first female Fellow was admitted to King’s in 1970. In 1972 King’s, Clare and Churchill admitted their first women undergraduates. As our Librarian Tim Munby put it, ‘The women have been about the place for so long that it seems churlish to deny them the education’.

For a time there were quotas on the numbers of women accepted at King’s, but after a few years they were dropped and merit-based admission prevailed. In the first few years entrance scholarships were not offered to women, to temper the wind to the existing women's colleges, but by 1976 King’s found that they had to offer scholarships to remain competitive.

The Annual Report for 1972 reports simply that ‘The college admitted 10 graduate and 37 undergraduate women this year’, in a total of 452 students in residence. The 1973 Annual Report says ‘This is the second year of the admission of women to the college, and 90 women are in statu pupillari.’ In a spirit of true equality, even when the 1972 class started taking Tripos exams in 1974-75 the performance tables in the College’s Annual Report did not record the performance of women versus men. In fact by 1975 the Annual Report wasn’t even recording how many of the students admitted each year were women.

The College reported its first female Fellow, Joanna Ryan, in 1970.

Tess Adkins came to King’s as Director of Studies in Geography, with the first women undergraduates in 1972. In 1981 she became the first female Senior Tutor of a once all-male Cambridge college.

The 1972 matriculation photo shows the first female undergraduates admitted to King’s, though one must look closely to distinguish them from the men.

In 1990 Andrea Spurling conducted an in-depth research project for the King’s College Research Centre on Women in Higher Education. No aspect was left unaddressed. The full report can be downloaded from the tab below.